In light of the recent intensification of statements in the media on the alleged danger now threatening the conservation of the Šnipiškės Jewish graveyard in Vilnius (hereinafter Cemetery), the Lithuanian Jewish (Litvak) Community (hereinafter LJC) feel it our duty yet again to present the main facts in the case and the LJC’s well-founded position based on those facts regarding the issue of the reconstruction of the Vilnius Palace of Concerts and Sports (hereinafter Sports Palace) and its adaptation as a conference center.

1. To date no work for the reconstruction of the Sports Palace has been carried out, and therefore no possibly negative impact on the graveyard which was destroyed in the 1950s is being effected at the current time. The remains of the Vilna Gaon were removed to the Vilnius Jewish cemetery located on Sudervės street long ago and his headstone is located there.

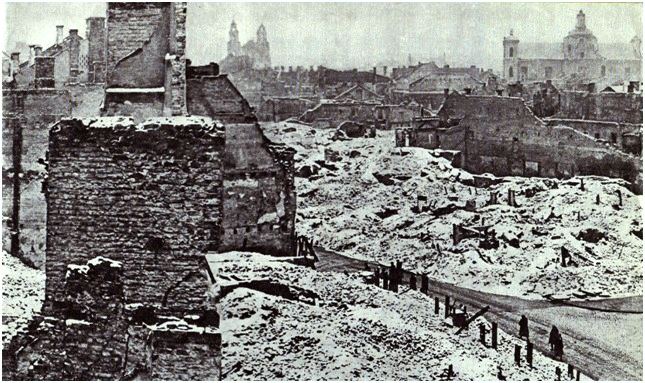

False statements and rumors have been circulating for some time, so again it is necessary to explain the headstones in the Cemetery were destroyed long ago and the Sports Palace was constructed there back in the Soviet era. At the current time only pre-planning proposals have been drawn up, which could serve later as the basis for a detailed technical project for the renovation and adaptation of the Sports Palace which will be carefully examined and assessed by competent institutions.

2. The Cemetery is entered on the Registry of Cultural Treasures and has been declared a state-protected site, meaning any construction or reconstruction work in the area of the graves or in the buffer zone around it, and any plans for this sort of work, are carefully assessed and strictly controlled under the provisions of the law of the Republic of Lithuania on protection of real estate heritage and the specific requirements of a special protection plan for this Cemetery.

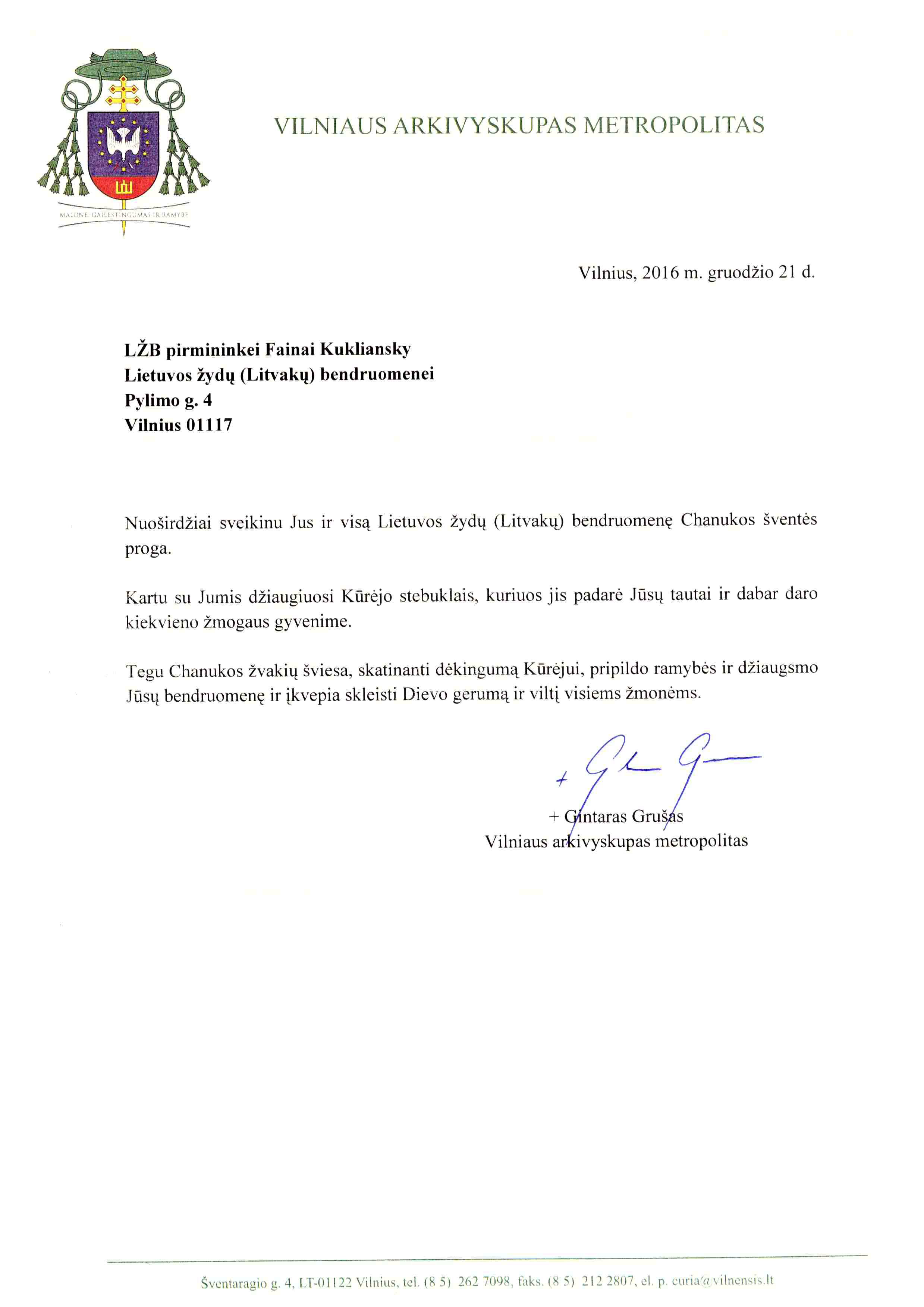

3. This special protection plan for the Cemetery was prepared under the requirements and principles contained in a protocol agreement signed on August 26, 2009, by the leaders of the LJC, the Committee for the Preservation of Jewish Cemeteries in Europe and the Cultural Heritage Department under the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture. All these institutions share responsibility for keeping the agreement and ensuring sufficient authority for doing so.

4. The protocol agreement of August 26, 2009, resolves that:

4.1. Earth-moving work is forbidden in the Cemetery;

4.2. Three additional possible buffer-function zones are defined; the Sports Palace falls into zone A where earth-moving work is proscribed except in cases involving engineering construction (utility pipeline, transportation and communication infrastructure) and/or work to maintain the Vilnius Sports Palace. Jobs involving the movement of earth require consent by the LJC and must be accomplished in the smallest scope possible. All work involving the movement of ground must be done under the supervision of an archaeologist and an authorized LJC delegate. To insure adherence to this requirement, the LJC makes all decisions regarding the conservation of the Cemetery and plans for the reconstruction of Sports Palace only with the knowledge and consent of the Committee for the Preservation of Jewish Cemeteries in Europe.

5. The Vilnius Sports Palace was constructed in 1973. The building and the Cemetery upon which it was built have been listed on the Registry and are protected as a cultural treasure since 2006.

6. According to the original construction documents presented to the LJC, the foundation of the Sports Palace extends 7.37 meters underground, so most likely all burials there were destroyed during building construction. Therefore pre-planning proposals for reconstruction of the Sports Palace are based on the assumption burials do not remain under the building. Despite the low likelihood there are still graves under the building, in the event of actual reconstruction of the Sports Palace the LJC will demand earth-moving work be of minimal scope and conducted under the supervision of representatives of the Committee for the Preservation of Jewish Cemeteries in Europe.

Therefore, bearing in mind that:

1) existing burials were destroyed during construction of the Vilnius Sports Palace;

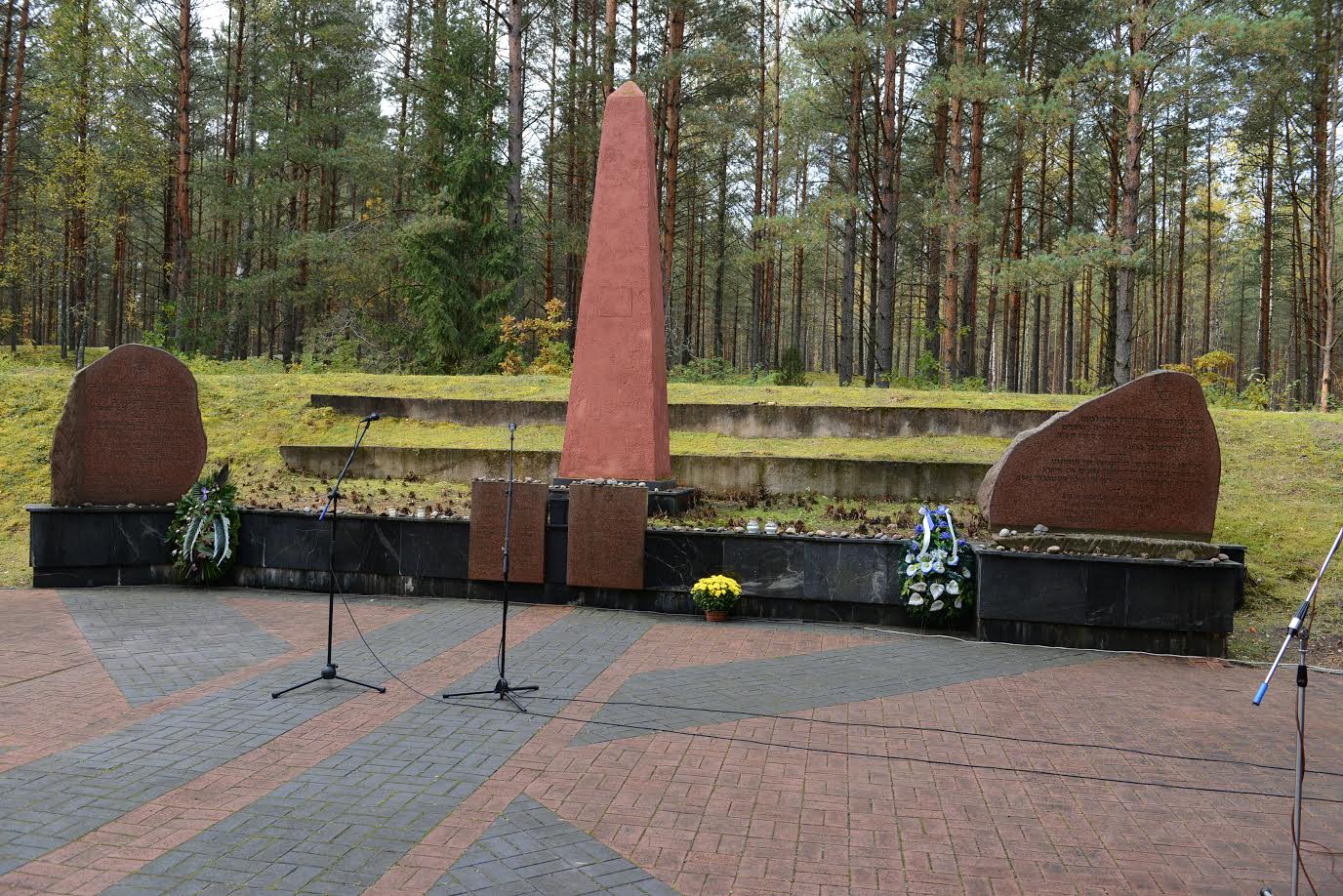

2) currently not a single headstone remains at the Cemetery (the last monuments were torn down back in 1955), the Cemetery territory is in disrepair, and there are no signs in the huge territory of the Cemetery testifying to its history except for a symbolic statue and an information plaque set up a few years ago;

3) the Sports Palace building along with the Cemetery surrounding it are listed on the Registry of Cultural Treasures and it cannot be torn down, but in its current state cannot either be used and requires renovation;

4) the abandoned Vilnius Sports Palace is in a state of ruin and is unbefitting the city center and the Cemetery, and stands as a horrid symbol recalling the Soviet era when the headstones of the Cemetery were destroyed and the human remains there disturbed;

The Government of the Republic of Lithuania have the right to do as they please with the property in their possession, and certainly the right to merely consider the reconstruction of the Vilnius Sports Palace, adapting it for one or another use, and the LJC has no legal foundation or rational arguments for quelling these activities. Instead of engaging in unconstructive criticism, the LJC is undertaking all measures to insure these plans and their possible realization do not violate Jewish law and tradition, and believes the Government of Lithuania, as a responsible institution with a vested interest in maintaining its reputation, will also exhaust all efforts so that the project is carried out to the highest standards of transparency, quality and respect for heritage. If the project is carried out appropriately, the LJC would achieve our goal of preserving the Cemetery:

1) establishing in city planning and physically demarcating the limits of the Cemetery;

2) renovating the territory of the Cemetery and setting up walking paths there in line with Jewish law and tradition;

3) erecting a commemorative composition including the names of the people buried in the Cemetery;

4) installing necessary educational and information material on site.