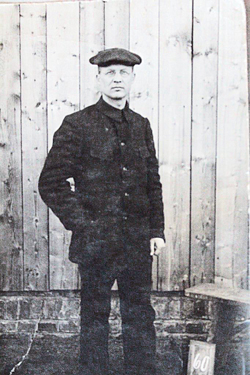

A commemorative plaque was unveiled on October 5 to honor the memory of Volf Kagan, Jewish Lithuanian soldier and two-time recipient of the order of the Cross of Vytis, in the town square of Balbieriškis (Balbirishok) next to the local government building in the Prienai region of Lithuania. Volf Kagan (1900-1941) came from this town.

According to Balbieriškis Tolerance Center director Vitas Rymantas Sidaravičius, the plaque honors both Kagan and the former Jewish community of Balbieriškis. The plaque was the brain-child of Lithuanian journalist Vilius Kavaliauskas, author and editor of articles and the book “Pažadėtoji žemė – Lietuva” [Lithuania: The Promised Land] about Litvaks, and was financed by the Prienai regional administration. Lithuanian Jewish MP Emanuelis Zingeris attended the unveiling ceremony as did Prienai regional administration head Alvydas Vaicekauskas, deputy regional administration head Algis Marcinkevičius, representatives of the Kaunas Jewish Community, Vilius Kavaliauskas, Prienai regional culture, sports and youth department director Rimantas Šiugždinis, Išlaužo žuvis company director Rimantas Jurgelionis, Balbieriškiis parish head priest father Remigijus Veprauskas, head town doctor Angelė Sidaravičienė, Balbieriškis alderwoman Sigita Ražanskienė, members of the aldermanship council, Balbieriškis primary school students and teachers, Culture and Leisure Center staff and local residents.