The deportations of Lithuanian residents touched every ethnic group in the country, the Jews included. On 14 June 1941, some 3 thousand Jews were exiled from Lithuania.

In the fall of 1941, a train carrying a cargo of exiles from Lithuania rolled in to the foreign and cold city of Syktyvkar. Ravaged by famine and disease, they had travelled thousands of kilometres in tightly sealed cattle cars. Entire families would die from starvation. Those deported on orders from Joseph Stalin, the ‘Father of Nations’, included the Abramovičius family of Jews from the town of Tauragė (Taurogi shtetl): mother Taube-Leja and her three kids, the oldest son Leibas aged 12, the middle son Abramas, 8, and the youngest Aronas, just five.

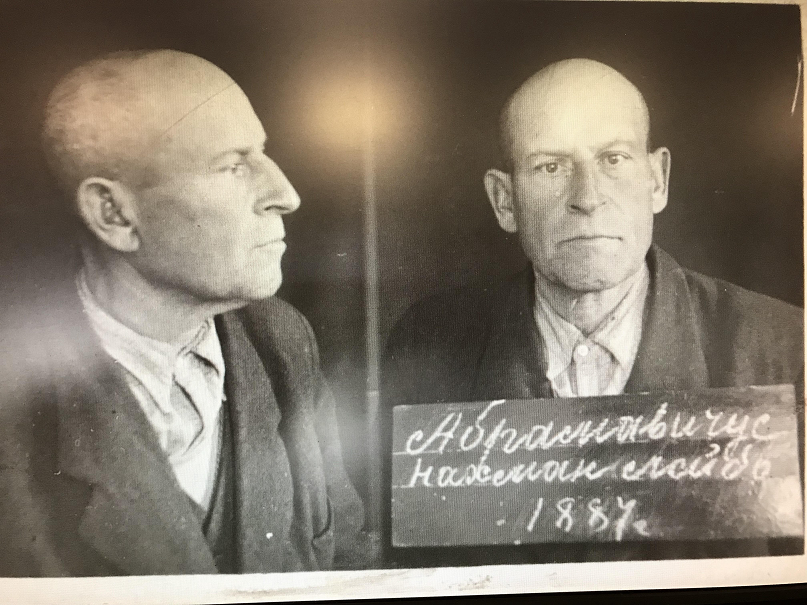

Abramavichius Nachman son of Leib

1887

Her husband Nachmanas was sent to the Reshoty camp, yet he was taken in a different car for male arrestees. The car with the man of the family was detached somewhere along the road. And so they lost each other for good.

The first years in exile were very harsh: the families were uprooted from the familiar environment and the climate they had gotten used to; they had virtually no personal property, no accommodation, very little food, plus there were only few who could speak Russian. Without men, who were kept in camps, the whole burden would usually be borne by women.

As a result, year one of exile saw the highest mortality rate, reaching 20 per cent. After that, people became gradually acclimated, they would tend to their accommodation, find additional sources to scrape by, normalise their relations with the local people.

Taube-Leja and her kids spent their first months there in complete misery. They would exchange golden jewellery that they had managed to smuggle in for food: bread, potatoes, and flour. Taube-Leja’s inherent ingenuity and tailoring skills came in handy in that regard. Her neighbours told her that one of the families of exiles from Lithuania were selling a Singer sewing machine in good condition. She made a deal and swapped the Singer for a golden bracelet, a gift from her beloved husband Nachmanas for her fortieth. Taube was a master of all trades, be it sewing, embroidering, knitting, or cooking.

Taube-Leja started making tailor-made undergarments. Her clients included theatre actresses, party workers, and wives of town officials. They helped her find a job at a local café/diner. During the day, Taube-Leja would work at the diner, and would sew at night and on weekends. Sometimes she could even take something from the café/diner home.

The boys grew up to be healthy, well-mannered, and neat. Leibas and Abramas Abramovičius showed an aptitude for business at a rather young age, while Aronas’s main passion was music.

Their apartment was dominated by a huge black piano – the centrepiece in the otherwise shoddy environment. Apart from attending a music school, Aronas also took vocals classes at the studio of the town’s pioneer house. The neighbours said that the youngest son Arkadijus was also the one they loved best. Aronas (Arikas) has an extraordinarily beautiful tenor voice! Of all the boys, he was the best at performing Lenski’s arias from Eugene Onegin, Vladimir’s arias from Prince Igor, Tchaikovsky’s ballads; he could also play the guitar and the violin …

The brothers Abramovičius finished technology schools and institutes in Russia. Their Jewish mother created a happy and comfortable home for everyone. She was the first defender, adviser, and friend to her children. That is why the Jewish mother, in the words of Halacha, passes the bond with the Almighty on to her children. From one generation to the next.

Taube was a brave and smart woman, raising three sons all by herself. She would invest everything she earned in them, sparing no thought about herself. She sacrificed herself for her boys. Taube wrote multiple letters to Lithuania’s soviet and partisan institutions, asking to be allowed to repatriate to Lithuania and to have her registration at the special place of residence annulled.

She wrote her last letter in 1957: ‘I am old and painfully cannot stand the northern climate… It has been 15 years since my husband Nachmanas died…’ The soviet and partisan bodies would send their inquiries to the NKVD, and the answer would always be the same: Nachmanas Abramovičius had been a capitalist, a usurper, and landowner – an enemy of the Soviet regime. Taube would be denied permission to return to Lithuania.

Nachmanas Abramovičius was born in 1887 in Eržvilkas, 25 km away from Tauragė. In 1922, there were about 222 Jews living in Eržvilkas, accounting nearly 50% of the town’s population; they had their own Jewish school, library, and synagogue. The Abramovičius family was engaged in the fertiliser business, growing flax, and purchasing flax fibre.

When he was a teenager, Nachmanas and his father would tour farms – potential sellers of flax – several times per year. His father Leibas Abramovičius was preparing Nachmanas for a difficult business. In 1925 already, Nachmanas Abramovičius was a rich man and had a lot of real estate in Tauragė.

Tauragė between the two wars

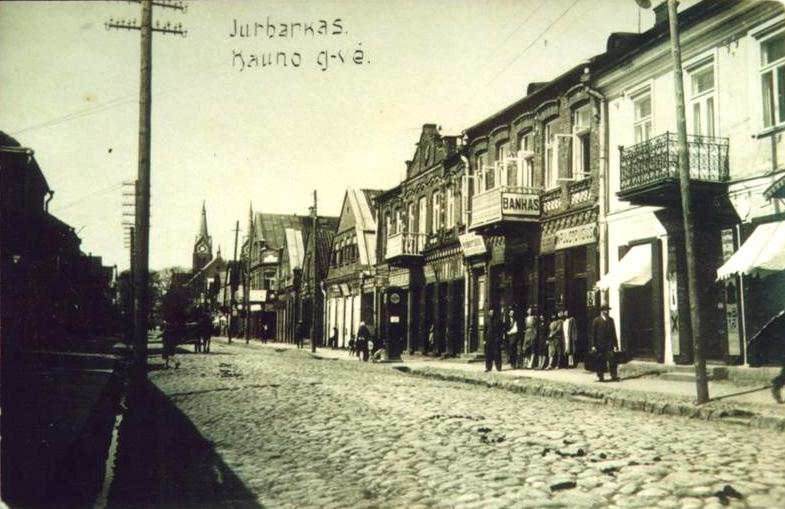

Nachmanas Abramovičius married Taube Berkover in Tauragė in 1925. Taube was born in Jurbarkas in 1900. Nachmanas Abramovičius was a close acquaintance of Taube–Leja and Šimonas Berkoveras of Eržvilkas. Taube’s family resided in Jurbarkas at the time. The family name ‘Berkover’ means a ‘ship owner’ in Yiddish.

Jurbarkas. Kaunas Street

Before the war, 80% of all ships in Jurbarkas belonged to Jews. The Berkover family had a ship and engaged in the business of shipment of goods and passengers via the Nemunas to from Kaunas to Klaipėda and back.

Before they were married, Abramovičius had bought a homestead with a large wooden house and 26 hectares of land in Village Užakmeniai, 3 km away from Eržvilkas. On one side, the estate ran all the way to the River Šaltuona. This is where the Abramovičius family usually lived. A few years later, three sons – Leiba, Abraomas, and Aronas – were born.

They installed a hotel and restaurant in a large brickwork building in Tauragė. Another two wooden houses that the Abramovičius family owned in Tauragė were rentals. The hotel and restaurant was in the care of Taube and her relative. Abramovičius also owned some beer trust warehouses in Tauragė.

Nachmanas would spare attention nor pricey gifts for his beloved young wife Taube and his sons. Abramovičius was also known for his charitable work: he would make donations to the synagogues in Eržvilkas and Tauragė, to the Jewish health organisation Ezra, the Lithuanian Firearms Foundation. These were the quaint concerns that the Abramovičius family had lived with until 15 August 1940. In the fall of 1940, the Soviet authorities nationalised all of the family’s real estate and evicted them from their homestead in Village Užakmeniai.

On 11 June 1941, husband Abramovičius was arrested, and the NKVD operational staff passed a decision to deport his wife, Taube-Leja and children from Lithuania as well.

Part II

In the summer of 1941, thousands of Lithuanian citizens, many of them arrested between 14 and 19 June 1941, were shipped on to Kraslag in tightly sealed cattle cars. Many of the detainees who were old and frail died in transit to be buried at the side of the railroad tracks. A lot of them died in 1941–1942. It was only in late 1942 and early 1943 that they were ‘registered’ at a special meeting; as a result, many Lithuanian citizens were sentenced posthumously. Most of them were sentenced to 5 to 10 years in prison, while some were given the capital punishment and executed at Kansk prison by firing squad.

The camp administration controlled the camp sections through criminals. Executing and organising work was in the hands of convicted criminals rather than the camp administration. The criminals would impose their will on the administration at the camp, controlling the rest of the inmates and doing zero work, despite getting credit for it.

The number one cause of death was starvation, which went hand in hand with the most taxing physical labour: people would cut down trees, prune the timber at sub-zero temperatures, and transport the logs to designated sites (warehouses) by dented wood roads. Most of them died of exhaustion, vitamin deficiency, dysentery, and injuries suffered at the logging sites coming in as contributing factors.

In the beginning, the dead would be buried in coffins at the local Kraslag chapter. Later, for economy reasons, they would take the dead in coffins from the camp to the cemetery, where the bodies would be dumped and buried, and the coffins reused until completely worn out. Later still they decided to ditch even this bit of formality: the bodies would be heaped onto carts, brought to the graves to be dumped and buried there. No one would bury the dead in late fall and in the winter: the bodies would rather be heaped outside the camp fence, awaiting burial in late spring, when the ground became warmer.

A former inmate’s recollections of the Kraslag camp:

We worked 12-hour shifts. We were given pigweed rations twice daily, 0.5 litre each, as well as 600 grams of bread. Of course, we would not meet our targets during the first months, because we were not used to cutting crossties, and the woods were frozen solid. And if we failed to meet the production target, they would cut our rations. In the spring of 1942, people were so wasted they could barely reach the work site. People swelled up from hunger and cold and would drop from exhaustion, yet the doctors were not allowed to relieve people from work. Those who no longer could walk would stay at the camp, those who refused to work would be put into solitary where they would only get some pigweed and 300 grams of bread. The bread was foul, too, what with wood filings and oat flour, among other things, added to cut the flour.

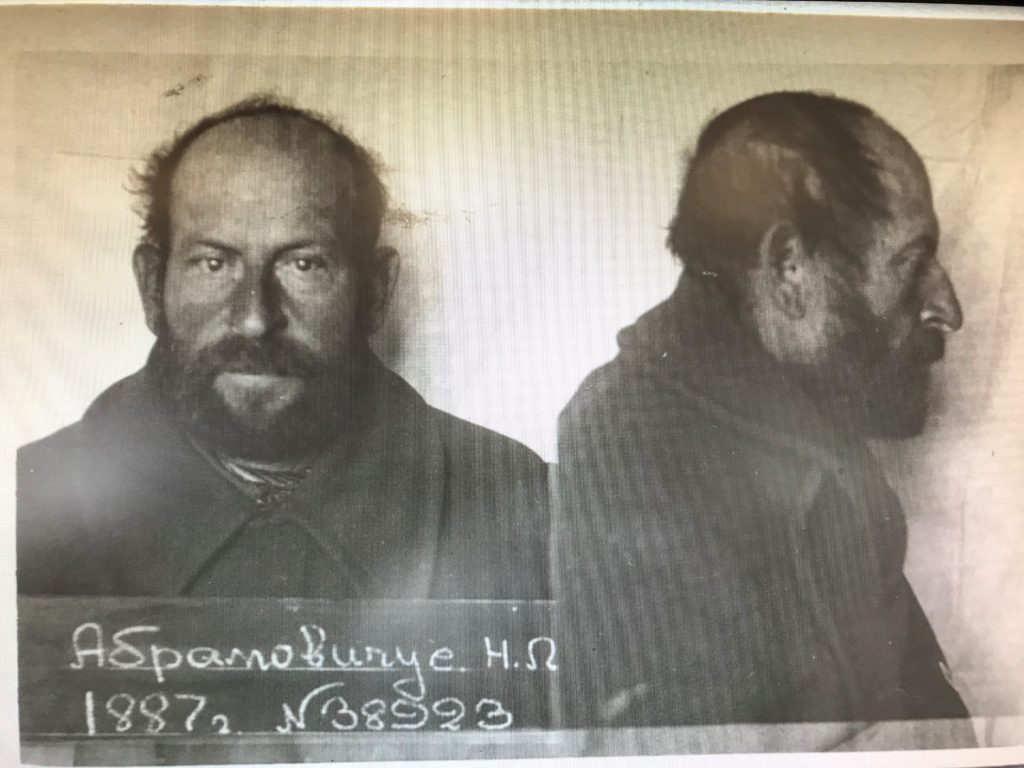

N. L. Abramovich

1887. No. 38923

One of the Lithuanian citizens who had been brought there by force was Nachmanas Abramovičius of Tauragė, aged 54, son of Leiba. He was assigned to Nizhniaya Poyoma camp No. 7.

His only crime was that he had worked well and with honesty his whole life. The verdict in Abramovičius’s case, passed on 17 February 1942 and approved on 18 May 1942, was that he was being sentenced to capital punishment through execution by firing squad, his property to be seized. A record of 30 May 1942 reads that the verdict had been changed to 10 years in camp.

Abramovičius most probably died in the winter of 1941/42 from starvation, cold, and disease. The verdict was registered only after his passing. Three different documents point to three different dates of Abramovičius’s death.

There were witnesses who said that Abramovičius always believed he would go back to Lithuania, to his home place in Eržvilkas and Tauragė.

On 22 June 1941, the Nazi troops entered Eržvilkas. There were some 50 Jewish families living there at the time. In just two weeks, the occupation authorities set up a provisional ghetto on a small Eržvilkas street, and on 15 August 1941 all of the town’s Jews were shut in the synagogue, after they had been ordered to take their necessities with them. However, a bunch of peasants soon arrived with carts on Nazis’ orders, took everything away from the Jews, and brought everyone to the neighbouring town of Batakiai. In September 1941, the Mažintai forest 700 metres off Batakiai saw the execution of the Jews of Eržvilkas – the children, the teenagers, the women, and the elderly.

Nachmanas Abramovičius died later, after the Jews of Eržvilkas has been executed by firing squad.

Notes:

Aronas Abramovičius was the father of Romanas Abramovičius, a multimillionaire and a patron. Romanas Abramovičius has inherited his interest in yachts from his grandmother, Taube–Leja Berkover.

The father of the author of this article, Alteras Taicas also spent time at Nizhniaya Poyoma, Section No 7 of Kraslager, between 1941 and 1946.

Geršonas Taicas