Photo: Lithuanian deportees en route to Siberia. Center: Family of B. and I. Jablonskiai. The only known photograph in Lithuania of a deportation cattle wagon.

by Romualdas Beniušis

This year marks 70 years since the third large post-war deportation operation Osen (Autumn) carried out by the Soviet security structures (MGB) on October 2 and 3, 1951, during which more than 16,000 people deemed “bourgeoisie,” including 5,000 children, were packed into cattle cars and deported to Siberia.

At that time, 39 children didn’t reach their places of exile. Their deaths marked the way along which Lithuanians were deported to Siberia. This time, the lists of deportees were entrusted to the local government administration and Party committees because it had become ever more difficult to find the “bourgeoisie” needed for carrying out the deportation plans. Thus the opportunity arose to include on the list of people to be deported those the local government didn’t like, the more educated, and even people who lived in the cities, carrying out personal grudges and to seize the property of the deportees.

Since only a few days passed between the confirmation of the lists and the beginning of deportations, the deportations began to be carried out without formal deportation cases which were drawn up later. The barely-literate locals who compiled the lists and usually foreign MGB officials who drafted the formal cases made endless mistakes in those documents, distorting surnames, dates of birth and so on, but this did not become an obstruction on the way to Siberia.

The Lithuanian Special Archive conserves the deportation case against the Kasperaičiai family who lived in the village of Imbarė near Salantai, who had rescued the Jews Basia Abelmanaitė and Rapolas Veržbolauskas from Salantai during the Nazi occupation. The case-file demonstrates the cynicism of Soviet occupational-regime officials and the loss of moral values by the people of rural Lithuania frightened and driven by the loss of our best people driven to collective farms.

The surviving record of the general meeting of the Imbarė Collective Farm which took place on July 12, 1951, with 75% of all collective farm members and representatives of the Salantai regional executive committee and Communist Party committees attending, shows the heavy atmosphere in the Lithuanian countryside at that time.

The meeting agenda had two items: 1) consideration and adoption of a letter from the collective farms of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic to comrade Stalin; 2) organizational and agricultural issues for strengthening the collective farm.

The letter to comrade Stalin was quickly discussed and adopted unanimously without much discussion, but agenda item number 2 was subject to much greater discussion.

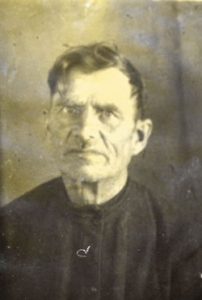

Photo: Pranas Kasparaitis in Siberia,

ca. 1951-1952. Photograph from his

deportation case.

From the record of the meeting: “Collective farm director comrade Antanas Galdikas provided an introductory word on this issue, noting the lack of organization on the collective farm, for example, trips made by collective farm members to market, not showing up for work on time and the general lack of discipline on the farm. The speaker noted it was the bourgeoisie element which exists at this collective farm that was especially hindering the rectification of these problems, and called for finally liquidating this element. But comrade Pranas Kasparaitis, who had come to be among the members of the collective farm at this time and even sat on the revision commission, hadn’t done anything good and only did harm to this collective farm. In conclusion, the harm done by this element, i.e., by this person, was to be seen in the fact he was using 3 hectares of collective farm land for his own purposes.

“The collective farm director called for removing this bourgeoisie element from the collective farm. After his statements, collective farmer Juozas Turauskas remarked comrade Kasperaitis was a ‘good’ person and he shouldn’t be cast out as a member of the collective farm because he had hidden two Jews during the German period, and that’s why he maintained contact with the Germans, in order to defend and preserve them.

“After his speech, Salantai regional party committee representative comrade Cepovas was asked to present his views, and noted comrade Kasperaitis hadn’t worked the lander, neither under the Germans or during the Smetona period, and had hired workers, and further that hiding Jews during the German period provided him with a profit, and this circumstance could in way be connected with Soviet policy, i.e., with the Soviet man. While hiding Jews, comrade Kasperaitis, at that time pretending to be a ‘Soviet man,’ perhaps sought for himself victims which he could turn over at any time to the Germans. Thus, comrade Cepovas emphasized, Kasperaitis’s behavior was in no way worthy of the appellation Soviet man. After comrade Cepovas left the podium, comrade Turauskas admitted he hadn’t understood comrade Kasperatis’s behavior correctly.

“After meeting participants unanimously expressed the wish to throw Kasperaitis out of the membership of the Imbarė Collective Farm as a bourgeoisie and harmful element who, even if indirectly through his lackeys, was harming the collective farm and might even have contributed to the recent destruction by fire of the flax warehouse, a resolution was adopted unanimously to remove him as a member of the Imbarė Collective Farm [sic] and to turn him over to the office of prosecutor for the theft of collective farm land and its exploitation for his own purposes.”

Although the Salantai regional executive committee annulled the decision of the members of the Imbarė Collective Farm in the former’s resolution dated July 28, 1951, also removing the person in question from the list of the “bourgeoisie,” this exerted no influence over the future fate of the Kasperaičiai family.

On October 2, 1952, Pranas Kasperaitis (1888-1969), Sofija Kasperaitienė (1898-1972) and their minor daughter Kazimiera Kasperaitytė (1939-) as a “bourgeoisie” family doing harm to the collective farm system were loaded onto cattle car no. 1 on special train no. 97477 and following an exhausting 16-day trip in these unhygienic conditions arrived in the city of Achinsk in the Krasnoyarsk oblast. The efforts and appeals made by Jews in Vilnius who had been rescued, after they learned of the lot befallen their rescuers, could do nothing to stop this because the MGB structures almost never changed their decisions.

In 1941, when the Nazis had occupied Lithuania and had begun the mass extermination of Jews, Pranas Kasperaitis, a staunch Catholic, after discussing this with his wife Sofija and Salantai church vicar Antanas Simaitis (1887-1959), resolved to save the life of Basia Abelmanaitė (1910-) who came from a poor Jewish family in Salantai. Taking her to their home from the Šalynas manor where Jewish women were kept and used as labor by order of the occupational regime, the Kasperaičiai provided her temporary haven.

Photo: Sofija and Pranas Kasperaičiai with Basia Abelmanaite-Jankelovičiene, the Jewish girl they rescued (right), and their daughter Kazimiera at their family farm in Imbarė. ca. 1960s. Photograph from the archive of Gražina Kasperaitytė-Selkauskienė.

Four weeks later when the occupational power ordered all women working for local farmers be returned, Pranas Kasperaitis returned her and told her she would be provided a safe place if she were able to run away from her executioners. She soon managed to do so as Salantai auxiliary police led about 180 women from the Šalynas manor to their execution site at Šateikiai. SHe successfully reached the Kasperaičiai family farm and she was hidden and cared for there.

In April of 1942 the last surviving Jew of Salantai, R. Veržbolauskas (1895-1985), also found safe haven at the Kasperaičiai family farm. Sofija Kasperaitienė’s sister’s son Gediminas Būda brought him there hidden in the hay on a wagon. Abelmanaitė and Veržbolauskas spent several years filled with danger and fear at the family’s farm and lived to see the return of the Soviet army on October 10, 1944.

Photo: Sofija and Pranas Kasperaičiai with son Pranas at their home in the village of Plotbishche, 1957. Photograph from the archive of K. Kasperaitytė-Motužienė.

Kretinga resident and engineer Ignas Jablonskis (1911-1991) and wife Bronė (1918-1993) with their five children aged 4 to 14 were on the same deportation train with the Kasperaičiai family and Ignas Jablonskis had taken a photographic camera with him. The photographs he took and the written remembrances bring back from oblivion the stark challenges of fate which faced deportees: the starvation, freezing temperatures, degradation, humiliation and suffering during the journey and afterwards living in exile experienced by the passengers on the train of 32 cars.

On the morning of October 17 the train stopped at the first station in the city of Achinsk and everyone was ordered to disembark from the cars, take their bundles and assemble on the platform. About 800 people of all different ages, from babies only a few months old to the elderly in their 90s, did so. Soon thereafter a “white slave market” began, as the directors of the collective farms in Achinsk arrived and carefully looked over and selected the youngest and most fit for work among the deportees.

Elderly deportees and families with children which no one had selected were forced to spend the cold night on the station platform, despite the fact there were train cars standing right there with iron stoves. They spent the next day in the cold on the platform as well as snow swirled around in the air, until towards evening the remaining families with small children, the old people and people with disabilities were loaded onto trucks and began the journey to their final place of deportation. The trip from Achinsk to the village of Plotbishche 40 kilometers to the southeast over the taiga on flooded roads took several days until 11 families, 25 people in all including the Jablonskiai and Kasperaičiai families, reached their place of exile, the Red Star Collective Farm on the banks of the Chulym River.

The Jablonskiai family succeeded in getting a separate small house while the other deportees were placed with local residents in their impoverished apartments. In late fall it was proposed to the deportees they dig up frozen potatoes which became their staple food in the first winter of exile, since an entire day’s wages at the collective farm consisted of just a half kilogram of grain, only to be received at the end of the year. Some were able, to prevent the death of their children from starvation, to acquire some flour for bread from the director of the collective farm, but this happened rarely. Unable to withstand the hunger, people began eating the bark of willow bushes, they brewed tea from it.

The first victim of hunger was the 82-year-old man Pranas Keras from Lazdininkai village whom they deportees buried in an abandoned local cemetery, fashioning a coffin from rough-hewn boards from the logs used to construct a farm building. The next morning, as usual, everyone again gathered in the hallway of the collective farm asking for flour for making bread. This is how the first winter of life in exile passed for the deportees, on the border between life and death, at down to 45 degrees below zero.

Photo: The Lithuanian deportees of Plotbishche village bury the first victim of deportation. Second from left is Pranas Kasperaitis, first from right is Sofija Kasperaitienė with daughter Kazimiera, 1952. I. Jablonskis’s photo from his personal archive.

In early 1952 the son Pranas Kasperaitis (1922-)arrived back to his family. He had volunteered for deportation to accompany his fiancée Stefanija Užčinaitė [sic]. Having served his sentence for selling a firearm he had discovered to partisans, he was released from the camp, and so it became easier for the family to feed themselves. When summer arrived the hard-working Lithuanians began to grow vegetables and potatoes in that earth whose fecundity they had never witnessed before, and one and another acquired poultry or livestock animals to enrich their lives of poverty.

On December 1, 1952, Pranas Kasperaitis wrote a plea for clemency to the chairman of the presidium of the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet. In the brief autobiography he included in the request, Kasperaitis described his origins among landless peasants, that from age 6 to 11 he had been a shepherd serving the rich, that he had no opportunities for education and later learned to sew under an experienced tailor, independent tailoring work, service in the Tsarist army and service in World War I, as well as his being taken prisoner in the Kaiser’s Germany. When he married his wife in 1922 he received as a dowry 9 hectares of land, and saved the lives of two residents of Salantai during World War II.

This plea was sent on to the Klaipėda section of the MGB, which issued a resolution confirmed by MGB major Petras Raslanas, the butcher of the Rainiai Forest, to reject the plea. Saving a few lives during the war meant nothing to the Stalinist system of repression which had murdered millions of completely innocent citizens of its own country.

Only in April of 1957 when Kasperaitis wrote a letter to the prosecutor of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was there a change in attitude towards the deportation of his family, although the decision to rehabilitate the family, allow them to return to Lithuania and to return their property to them was only made on April 18, 1958. Sofija and Pranas Kasperaičiai came back to Lithuania in April of 1958, while their daughter Kazimiera had already been returned to Lithuania in 1956 as a deported minor.

When they came back, the Kasperaičiai family initially shared their home with the family already living there, and later got all their property back. B. Abelmanaitė-Jankelovičienė left to live in Israel in the 1970s and never forgot her rescuers. After she testified concerning the great deed this family from Žemaitija had performed, the State of Israel awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations or Righteous Gentile to Sofija and Pranas Kasperaičiai on December 11, 1991 (posthumously), because despite mortal danger to themselves and their family they had saved people of Jewish ethnicity from the Nazi genocide during World War II.

Their names are engraved on the Wall of the Righteous in the Garden of the Righteous at the Yad Vashem Memorial Institute in Jerusalem. On September 16, 2002, the Lithuanian state recognized Sofija and Pranas Kasperaičiai and awarded them the Cross of the Life-Saver for their extraordinary resolution in saving those who were condemned to death.

Time is the best judge of good deeds which have no statute of limitations. The Israeli and Lithuanian states have commemorated Sofija and Pranas Kasperaičiai, so when will the people of the town of Salantai in Žemaitija do the same? When will a street, school, square or courtyard in Salantai bear the names of these courageous people who did not shy away from challenging the Nazi occupiers who brought the mass murder of innocent people to Lithuania?