Lithuanian Jewish Community chairwoman Faina Kukliansky says she and Rabbi Sholom Ber Krinsky never agreed on setting up a yeshiva in the Choral Synagogue in Vilnius. She says there was never any discussion about a Chabad Lubavitch Hassidic synagogue in Vilnius. Back in 2001 Rabbi Krinsky tried to set up a Hssidic synagogue but encountered opposition from Mitnagid Jews of Vilnius.

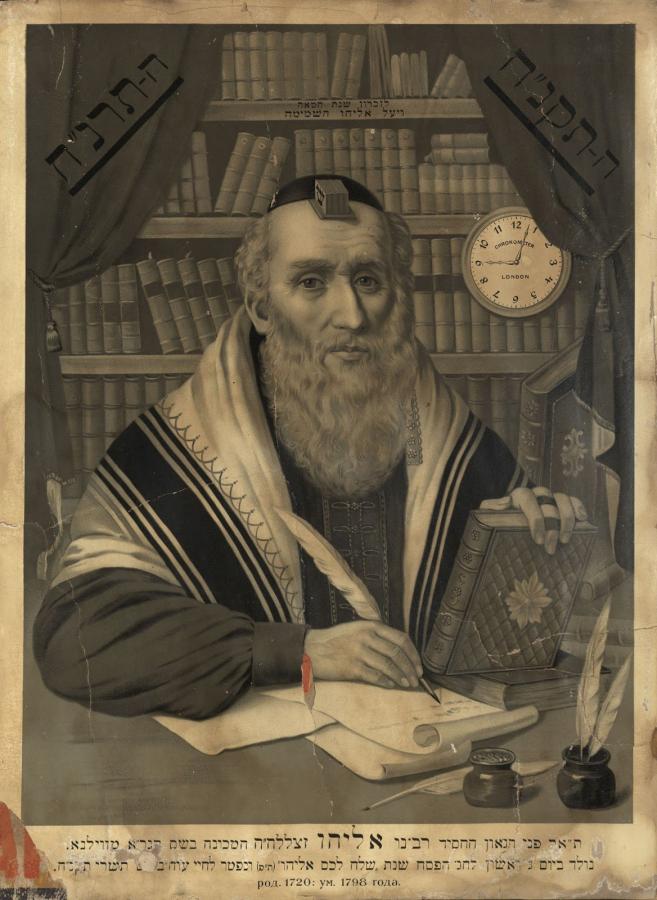

When Vilnius Religious Jewish Community chairman Simas Levinas announced in September, 2019, a yeshiva would be established at the synagogue, people began asking what kind of yeshiva it would be. During Rosh Hashanah Rabbi Krinsky spoke about the similarity between the Vilna Gaon and Chabad Lubavitch, but Lithuanian Jews know about the Litvaks’ opposition to Hassidism which began in the 18th century, about resistance to the movement which resulted in two groups of Jews, Hassidim and Mitnagdim.

These days Chabad rabbis are asked to work at Jewish Orthodox Mitnagid synagogues. This is acceptable. It was agreed with Rabbi Krinsky that he would conduct prayer services in the Litvak way. No one is opposed to the desire of opening a yeshiva. Chabad Lubavitch has its own building on Bokšto street [in Vilnius]. The rabbi may do whatever he likes there, for example, opening a yeshiva.

It’s not appropriate to open a Hassidic yeshiva at the Choral Synagogue in Vilnius, one of 100 synagogues which formerly operated in Vilnius, and one where the Mitnagid creed has always dominated, and all the more so since there was not even any agreement about this.

Two hundred years ago the Hassidic worldview also encountered opposition based on cabalistic interpretations which seemed to erase the line between good and evil, between the sacred and the profane. Dr. Aušra Pažėraitė, an historian of religion and religious studies expert, says the rapid spread of Hassidism in Eastern Europe didn’t last long and elicited a passionate opposition whose epicenter was Vilnius:

“Open conflict began when a Hassidic group which had operated in secret in the city for several years went public and caused huge confusion within the community. The Vilna Gaon himself was invited to a meeting of the community’s board of directors.

“In 1776 there was a congress of rabbis held in Vilnius presided over by the Vilna Gaon, and a decision was adopted to engage the largest Jewish communities in Lithuania and Byelorussia in battle against the Hassidim, and to send out circulars against them.

“In 1797, however, the Vilna Gaon died. The war didn’t end: the day after the Gaon’s funeral a meeting was called in Vilnius which not only resolved to ban Hassidim but also to no longer consider them ‘Children of Israel,’ ‘not to share bread or wine with them,’ ‘not to accept them as members of associations,’ not to allow them to hold any posts within the community, and so on.

“The students and followers of the Vilna Gaon continued throughout the 19th century to develop an authentic form, now known as Litvak form, of Judaism in which the modern Volozhin yeshiva founded by the Vilna Gaon’s student Rabbi Haim and its ‘graduates’ played an ever greater role. Efforts were undertaken to strengthen Torah study.”

In the late 19th and early 20th century an authentic Litvak Judaism developed, known in the world as yeshiva Judaism, and the “yeshivists” were often called Litvaks, even if they hadn’t come from Lithuania, and were further identified as “non-Hassidim,” because the Hassidic worldview and life-style were wholly contrary to their ideals.