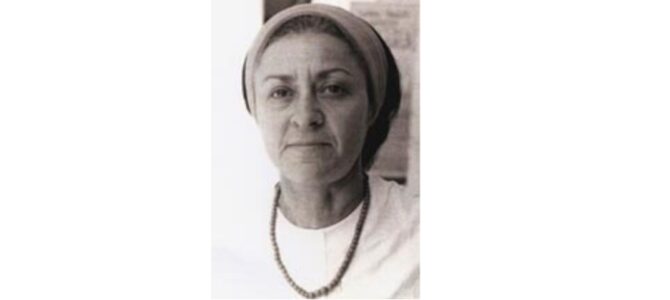

by Zelda Kahan Newman

Last updated June 23, 2021

In Brief

Born February 20, 1925. Rivka Basman’s mother died when she was five. Her younger brother was ripped from her hands and murdered by the Nazis, and she escaped from the Nazi death march. After the war, she helped the illegal immigration movement to what was then Palestine. During that time, she met and married the painter Shmuel Ben-Haim, who designed every one of her books. The couple lived on Kibbutz Ha-Ma’apil for sixteen years, where she taught schoolchildren. During the 1960s, she studied comparative literature at Columbia University for one year, and later went to Russia, where her husband was Israel’s cultural attaché. In Russia, she furthered clandestine contacts between Soviet Yiddish writers and the outside world. After her husband died, she added Ben-Haim to her name.

Family and Education

Rivka Basman Ben-Haim was born in Wilkomir (Ukmerge), Lithuania to Yekhezkel and Tsipora (née Heyman) on February 20, 1925. Her mother died in 1930, and her father remarried; he and his second wife had a son, Aharon (Arele).

As a child, Rivka attended a Yiddish-speaking folk-shul, and she and her classmates read and delighted in the poems and stories of the Yiddish woman writer Kadya Molodowsky. Even then, she wrote poems in Yiddish. She continued studying in a Lithuanian gymnasium (academic high school), but in 1941, before she could graduate, her family moved into what later became the Vilna ghetto. She spent two years in the ghetto, where she met the poet Abraham Sutzkever and read him her poems in Lithuanian and Yiddish. He encouraged her to write only in Yiddish and was her mentor and friend till his death.

The Holocaust

When the Vilno ghetto was liquidated, Rivka was sent to Kaiserwald, a forced labor camp for women in Riga. While in the camp, she and two others decided that each would do something every day to lift the spirits of the women in the camp: one sang a song, one danced, and Rivka recited a poem she had composed that day (“Remembrance,” The Thirteenth Hour, pp. 12-13). When Kaiserwald was liquidated, she managed to rescue her poems by rolling her copy of them under her tongue. She later said of these poems that they are “not sublimated enough”: they are a cry from the heart but not artistic enough to be considered good poetry. She plans to leave them to Yad Vashem, where they will serve as historical documents.

Rivka’s father (b. 1897) was murdered by the Germans in Klooga, a camp in northern Estonia, shortly before the Allied victory. Her brother Aharon was murdered by the Germans when he was about eight years old.

Marriage and Immigration to Israel

After World War II, Rivka spent two years in Belgrade (1945–1947), where she married “Mula” Shmuel Ben-Haim. There she helped him run the Belgrade Berihah (Heb. “flight”) station for moving Jews out of Eastern Europe for illegal immigration to Palestine. To avoid detection from Interpol, Mula took on her name, Basman.

Upon arrival in Israel in 1947, the couple became members of kibbutz Ha-Ma’apil. Mula, who had joined the Haganah, became an active soldier in the War of Independence, and Rivka helped defend her kibbutz when it was attacked.

After the war, Rivka studied at the Seminar Ha-Kibbutzim in Tel Aviv, from which she received a teaching diploma. She taught children on Kibbutz Ha-Ma’apil, where the couple lived for sixteen years. At the same time, she published poetry and was a member of the Yiddish poets group, Yung Yisroel (Yid., “Young Israel”).

In 1961, Rivka and Mula moved to New York City so she could study English and comparative literature at Columbia University. From 1963 to 1965, when her husband was Israel’s cultural attaché to the Soviet Union, Rivka taught the children of the diplomatic corps in Moscow. At the same time, she furthered clandestine contacts between Soviet Yiddish writers and the outside world.

Basman Ben-Haim’s Poetry

Rivka composed her first book of poems while she was still a member of Kibbutz Ha-Ma’apil; the rest were written after she had left the kibbutz. Her husband designed and illustrated all of her books as long as he lived, and she has used her husband’s prints in every book she has published since then. After his death on October 7, 1993, Basman added his family name to hers and became known as Rivka Basman Ben-Haim.

Basman Ben-Haim is a singularly non-ideological poet. She elected to live in Israel after the Holocaust and her poetry shows she feels rooted in Israel. But the political movements and social trends of her second home are absent from her work.

The first volumes of Basman Ben-Haim’s poetry contained poems that were rarely more than one full page. They have meter and are rhymed. Her innovative use of language often involves juxtaposing ordinary elements of language in extraordinary ways, e.g., Di Shtilkayt Brent, The Silence Burns. Biblical figures and hints of homiletic Jewish stories can be found scattered throughout her poetry, but these serve as metaphorical tools, not as themes. Her poetry is elegiac and lyrical. The elements of nature, trees and flowers, the sea and rain figure prominently.

Until she was about 80 years old, most references to the Holocaust in her poetry were oblique (for example, “Poems Too,” The Thirteenth Hour, p. 49, where she says “balm cannot be found.”) But as the years progressed, her reluctance to speak openly of the Holocaust diminished. In her poem “Sixty Years Later” (Poetry of the Holocaust, pp. 145-148), she explained that when she realized that she and those like her were “the last witnesses on earth/who saw and heard it all,” she allowed herself to speak more directly about what she saw, what she did, and how she felt. She identified Musye Miryem Daiches as the wonder-child who danced for the women-inmates every night; she spoke of her own poetry recitals, and she said “God, too, wore a yellow star-/How then could He save His children?” In 2020, Basman Ban-Haim finally devoted an entire book, A Bliyung In Ash (A Bloom In Ashes) to her experiences in the Holocaust. Dedicated to the brother who was “ripped out of her hands” and “burned up” (murdered), the book contains poems written during the Holocaust and poems and prose about her experiences during the Holocaust. She speaks openly of her shattered dream to be re-united with her father and the sense that those who “survived” did not really survive at all.

For all that Basman Ben-Haim’s early life was shattered, she remained optimistic. She and those who shared her fate found new lives. They maintained and created friendships; they found love and created families. On the whole, her poetry radiates a sense of calm and comfort: she found calm in identifying with the natural world, and comfort in friendship and in love.

One of the recurring themes in Basman Ben-Haim’s poetry is the nature of time. In her poem Arum A Refreyn (Concerning a [Musical] Refrain), she says about the refrain of the Yiddish song: “What was, was, and is gone”: “I don’t agree. /What was is with us still.” (See https://yiddishpoetry.gc.cuny.edu for the original and my English translation.)

Full article here.