There’s a larger-than-life fresco painted on the wall of a building on Kęstutis street in Kaunas featuring a portrait of celebrated Israeli poetess Lea Goldberg, with a poem by her in Hebrew and Lithuanian. Her family fled their home in this building 85 years ago, with Leah making aliyah and settling in Tel Aviv in 1935, after receiving PhDs from universities in Bonn and Berlin in Semitic and Germanic languages.

Now the Lithuanian city is scheduled to become the European Union’s honorary European Capital of Culture for the year 2022. Now, in the run-up to that auspicious year, local and visiting Jews in Kaunas held a celebration of, perhaps, the town’s most famous poet, as well as its lost Jewish heritage.

Bella Shirin, who has been appointed “ambassador” of Kaunas, Capital of European Culture 2022, recited in selections from Goldberg’s corpus in Hebrew to musical accompaniment. Israeli exchange student Shahar Berkowitz sang Goldberg’s work.

More than 30,000 Jews called Kaunas home on the eve of World War II, making up 25% of the city’s population. The provisional capital of Lithuania was known throughout Europe for its Jewish institutions of culture and education. Almost the entire Jewish population was exterminated during the Nazi occupation. Around 2,000 Jews came back to Kaunas after the Holocaust.

The fresco celebrating the apartment building where the Goldberg family lived until 1935 was created by Linas Kaziulionis. It’s 30 feet wide and 45 feet tall. The left side features a translation to Lithuanian of the Hebrew poem on the right side of the poet’s portrait, Oren, or Pine.

Israeli ambassador to Lithuania Yossif Avni-Levy said at the event: “If the great poet Lea Goldberg, who missed this beautiful city her entire life, could see her face on this street where she lived as a child, she would feel great happiness.”

The poetess’s parents were Abraham and Cilia. Abraham Goldberg was senior economist at an insurance company before World War I. As with most other Jews, the Goldberg family was “evacuated” from the front, meaning Lithuania in this case, during the Great War, into the interior of Russia. Lea was three years old when the family was forcibly deported from Kaunas. When they returned after the war and the defeat of Germany, Lea’s father was tortured by Lithuanian soldiers who simulated his execution on ten consecutive mornings, accusing him of being a Communist. Lea wrote the experience broke her father mentally, with what we would now call post-traumatic stress syndrome, which developed into a deeper mental illness.

Lea GOldberg reportedly never married and emigrated to Palestine in 1935, where her mother arrived in 1936, although some sources claim she was married briefly to the journalist Shimei Gens, born in the now submerged Jewish shtetl Rumšiškės, aka Rumshishok. She is reported to have lived her entire life with her mother after making aliyah.

Goldberg, whose parents knew multiple languages but not Hebrew, had an early affinity for the ancient language of the Jews, although the language at home was most likely Yiddish, and attended a Hebrew-language school. She began writing Hebrew poetry as an elementary school pupil. Her poetry is suffused with a sense of melancholy with an underpinning of optimism, often touching upon lost love, with a sense of longing for love and light lost, but perhaps not interminably. Her work is marked by an aesthetic intellectualism on the margins of modernity. Perhaps not coincidentally she hooked up with a group of Zionist Hebrew poets of Eastern European origin known as Yachdav (Hebrew: יחדיו “together”). This group was led by Avraham Shlonsky and was characterized by adhering to Symbolism and especially in its Russian Acmeist form, and in rejecting the style of Hebrew poetry common among to the older generation, particularly that of Haim Nachman Bialik.

She published nine books of poetry, six academic books, two novels, twenty children’s books, three plays and much more. With exemplary knowledge of seven languages, Goldberg also translated numerous foreign literary works exclusively into Modern Hebrew from Russian, Lithuanian, German, Italian, French and English. Of particular note is her magnum opus of translation, Tolstoy’s epic novel War and Peace, as well as translations of Rilke, Thomas Mann, Chekhov, Akhmatova, Shakespeare and Petrarch, plus many other works including reference books and children’s stories. Among the European classics Goldberg translated into Hebrew are Gorky’s Youth, Chekov’s Tales, several plays and sonnets by Shakespeare, Petrarch, Ibsen’s Peer Gynt and the Old French classic Aucassin and Nicolet, and many others.

Goldberg worked as a high school teacher and earned a living writing rhymed advertisements until she was hired as an editor for the Davar il-Yladim children’s magazine and Al ha’Mishmar. She also worked as a children’s book editor at the Sifriyat Po’alim publishing house while also writing theater reviews and literary columns. In 1954 she became a literature lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, advancing to senior lecturer in 1957 and full professor in 1963, when she was appointed head of the university’s Department of Comparative Literature. She translated many Lithuanian folk-songs into Hebrew as well.

She died on January 15, 1970. Goldberg received the Israel Prize posthumously, her mother accepting the prize for her.

Goldberg’s poems have been translated into various languages. Poems in English translation are included in T. Carmi (ed.), Penguin Book of Hebrew Verse (1981) as well as in Modern Hebrew Poem Itself (2003). Mikhtavim mi-Nesi’ah Medummah was translated into German (Briefe von einer imaginaeren Reise, 2003). For further English translations of her works, see Goell, Bibliography, index.

Her face adorns Israel’s 100 shekel bill.

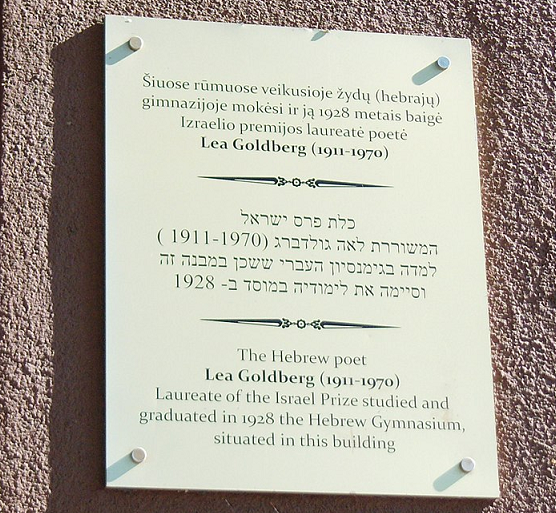

There is a plaque commemorating the poetess on wall of the former Hebrew gymnasium she attended in Kaunas.

Journalist’s identification.