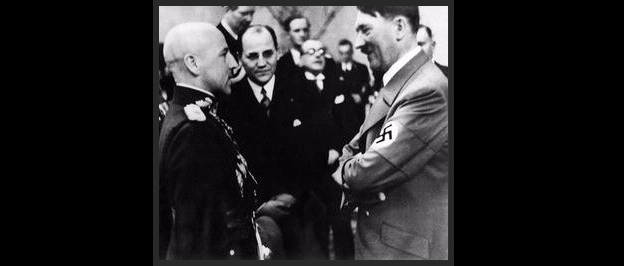

Note: The author of the following opinion piece identifies as a Jewish woman and is a member of the Šiauliai City Jewish Community, which is not a constituent member of the Lithuanian Jewish Community. Her views are not shared by the Lithuanian Jewish Community in any way and are presented here only in the interest of informing our readers of arguments for commemorating Holocaust perpetrators in Lithuania. Kazys Škirpa, the person in the middle to the left of Adolf Hitler in the photograph above, was a leading proponent of Nazi ideology and worked closely with the German Abwehr, or military intelligence, to ease the invasion of Lithuania by the Wehrmacht during World War II. The Vilnius city council is planning in the next few days to again address the issue of the known Nazi collaborator’s name being honored as a street name in the center of the nation’s capital. A similar move by Vilnius city council members several years ago was shot down before it came to a vote.

Photo: Škirpa celebrating Hitler’s 50th birthday, April 21, 1939. Note Lithuania Lithuania acquiesced to Hitler’s ultimatum and handed the Memel region, aka Klaipėda, back to Germany on March 23, 1939. Škirpa is on the far right in the photograph. Photo from Kazys Škirpa’s own memoirs in the book “Lietuvos nepriklausomybės sutemos (1938-1940)” [“The Twilight of Lithuanian Independence (1938-1940)”], Chicago-Vilnius, 1996.

Changing the Name of Škirpa Alley: A Hasty Initiative

by Kamilė Šeraitė, councilor, Vilnius city council

The Holocaust will remain Lithuania’s tragedy through the centuries, not just for the families touched by tragic fate whose descendants carry in their heart the yellow star of David, not just for the members of the Jewish community who have fought many long years for the memory of each innocent life which perished, but as the tragedy of our people.

The Holocaust is a topic about which most of us avoid speaking because it is too sensitive and we are afraid to offend, because we don’t know all the answers, so we remain silent, but when we do try to speak we often make mistakes and everything which is even remotely connected with this topic we see as painted black, even when the edge of a sheet of paper is barely stained and we through it in the trash can.

And this is the way we act towards the founder of the first Lithuanian Republic, towards volunteer soldier and diplomat Kazys Škirpa, a person who founded the independent state and opposed the Soviet occupation, although [he is] judged in various ways for the anti-Semitic expressions in some of the documents of the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF).

There are several problems where for which the historians have not presented final answers. Documents attributed to Škirpa were neither written in his name nor signed by him. Also, no one has proven what influence these LAF documents had (if they had any at all) or whether they somehow encouraged the genocide of the Jews in Lithuania. It hasn’t been determined they were even distributed in Lithuania, and if they were, how widely they were.

It cannot be forgotten the communication between the centers of the Lithuanian uprising and the LAF center in Berlin was, at that time, according to historical researchers, very limited: getting across the border with Germany vigilantly guarded by the Soviets was very complicated and not many people managed to do it, and information was passed orally, not by written instructions.

One of the LAF messengers who did manage to cross the border, reach Berlin and then return to Lithuania was Mykolas Naujokaitis, a member of the general staff of the Vilnius LAF headquarters. He has left behind a “testimonial statement” under oath, notarized by California notary Stephen C. Clark, which states “the Kaunas, the Vilnius LAF headquarters and the supreme headquarters of the LAF never issued any written calls and cautioned everyone not to distribute and not to make copies of calls appearing from unknown sources.”

This is confirmed by Pilypas Narutis, one of the leading members of the Kaunas LAF general staff and the author of “Tautos sukilimas’ [Uprising by the People]. He wrote: “The LAF, concerned with the continuity of state, sent an envoy from occupied Lithuania to Berlin, inviting the minister for Germany authorized by independent Lithuania to assume the duties of prime minister in the Provisional Government foreseen by the underground. In order to insure secrecy and conspiracy, the Vilnius, Kaunas and Supreme LAF headquarters did not write texts down [about this] and relied on personal contacts, and warned everyone not to relay programs or calls appearing from unknown sources.”

There has been no expert confirmation performed on the authenticity of the LAF appeals, their authenticity has not been confirmed, they are unsigned and their evaluation is a matter of controversy. Historians working on that period have presented facts on counterfeit documents made by the NKVD and Gestapo which were distributed as if from the LAF.

Because the June uprising of 1941 was attempted to restore the independent state of Lithuania, it was opposed by the Soviets who claimed Lithuania had “voluntarily entered” the Soviet Union as well as by the Nazis who wanted to turn Lithuania into lebensraum for settlement by Germans. Thus both parties sought to compromise the uprising and its leaders, employing falsification of documents and slander.

We cannot ignore the political context in which Škirpa operated. He operated when Lithuania was under occupation and under conditions of the war going on in Europe. He was the only diplomat in June of 1940 who dared visit occupied Lithuania and make direct contact with the anti-Soviet resistance. Soviet security was enraged and attempted to capture him, but he managed successfully to get out of Lithuania, then being terrorized by the NKVD.

In July of 1940 the Bolshevik regime rescinded Lithuanian citizenship for Škirpa, seized his property and assets in Lithuania and declared him their enemy. Three times (1941, 1942, 1944) the Gestapo used violence against him and kept him “behind barbed wire) right up till May 7, 1945. Unable to reach Škirpa now operating in the West, Communist propaganda continually libeled him beginning in 1945. It is difficult to believe this is still going on in independent Lithuania.

It is completely clear: Škirpa was not involved in the holocaust [uncapitalized in the original]. He wasn’t even in Lithuania until the fall of 1943 when German security issued him a brief permit to visit his ill mother. And that was the first and last time he briefly visited Lithuania. Moreover, the Chicago newspaper Draugas on June 25, 1941, when battles by the insurgency were underway in the streets of Kaunas, reported “Jews will not be persecuted,” “colonel Škirpa has forbidden the persecutions of Jews in Lithuania.”

How do we reconcile this public, incontrovertibly documented position of Škirpa’s regarding Jews with the anti-Semitic statements attributed to him based only on suppositions and interpretations which we do not find in public sources of information from that period, but only in some private archives? This question is at the very least worthy of further investigations by historians, but not of further interpretations by politicians.

Despite that, some members of the Vilnius city council are undertaking to provide answers to exactly these sorts of questions to which even history professionals don’t even have reliable answers. The accusations against Škirpa are not based upon incontrovertible evidence but upon ideological motives which correspond to the Soviet historiography tradition and the current political platform of the Kremlin.

The initiative to do away with the name of Škirpa Alley is at the very least a hasty initiative which is causing tension, dividing society and setting the public against itself. It was correctly observed that this “would be perceived … as a derogatory punishment to a person who is dead, who, it appears, did not commit great crimes. Resistance was only a crime in the eyes of the occupying power. Nonetheless there is a choice between giving or not giving the name, and presenting memory.”

In considering this question, we shouldn’t forget the person of Škirpa is inseparable from the Lithuanian state’s birth, development, tragic disappearance and resolute battle for the restoration of independence. He was the first Lithuanian military volunteer, the de facto [military] commandant of the city of Vilnius who at the age of 23 raised the [Lithuanian] tricolor on top of the Tower of Gediminas, which is why we celebrate Flag Day today.

Way back on October 25, 1919, Škirpa was awarded the Order of the Cross of Vytis, 5th degree, for bravery. He was the head of the [military] general staff in 1926 who opposed the December 17 coup d’etat to overthrow the democratic order. He was a brilliant military attaché and plenipotentiary minister in foreign countries, uncompromising in his defense of the interests of the Lithuanian state, never betraying them and never collaborating with the foreign invaders [sic].

Škirpa was the prime mover in the uprising of June, 1941, and this was the beginning of the anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi resistance [sic]. Living abroad, he actively took part in the political struggle for the restoration of Lithuania and in his articles and writings explained and defended the right of Lithuanians to restore the independence denied them. He left behind a valuable popular press, memoir and epistolary legacy which has not only never yet been published in Lithuania, but hasn’t even been researched adequately.

In judging statements uttered during the former period and under complicated historical circumstances, we cannot assume the role of judges [sic] and judge them exclusively through the prism of current ideology, public relations and politics. The public revision of the historical personages of Lithuania met by tragic fate, for example, Škirpa, Adolfas Ramanauskas-Vanagas and others, based on “clay” arguments [?] and sophistic arguments, is fully in keeping with the goals of the campaign by the Kremlin and their allies in the West to compromise Lithuania’s anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi struggle. All the more so because there is no lack in Vilnius of monuments and place names glorifying the true collaborators with the totalitarian regimes.

Full text in Lithuanian here.