Mass deportations to Stalin’s camps began on this day in 1941.

About 17,500 people were deported from Lithuania between June 14 and 18, 1941, (the fates of 16,246 have been determined so far), a number derived from the 4,663 arrested and 12, 832 people officially deported. The deportations were a huge loss and tragedy for Lithuania. Not all those deported were ethnic Lithuanians: about 3,000 Jews, according to various sources, were also deported and about 375 Jews died at the camps and in exile.

Jews deported to Siberia resisted the brutality and terror of the oppressive Soviet organs with a deep spirituality and faith. In 1941 about 1.3 percent of the total Lithuanian Jewish population were deported, and as a percentage constitute the largest group by ethnicity deported from Lithuania.

Santariškės Children’s Hospital doctor Rozalija Černakova tells the story of what happened to her grandfather and family. Her grandparents were deported with their families. Rozalija’s parents were still children when they were deported: her mother 11 and her mother’s brother 8. They were sent to the Altai region. That’s where Rozalija was born.

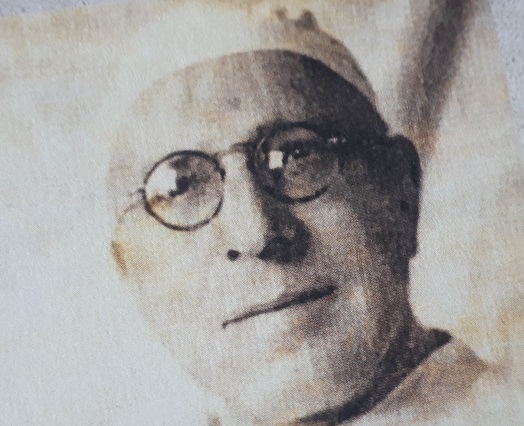

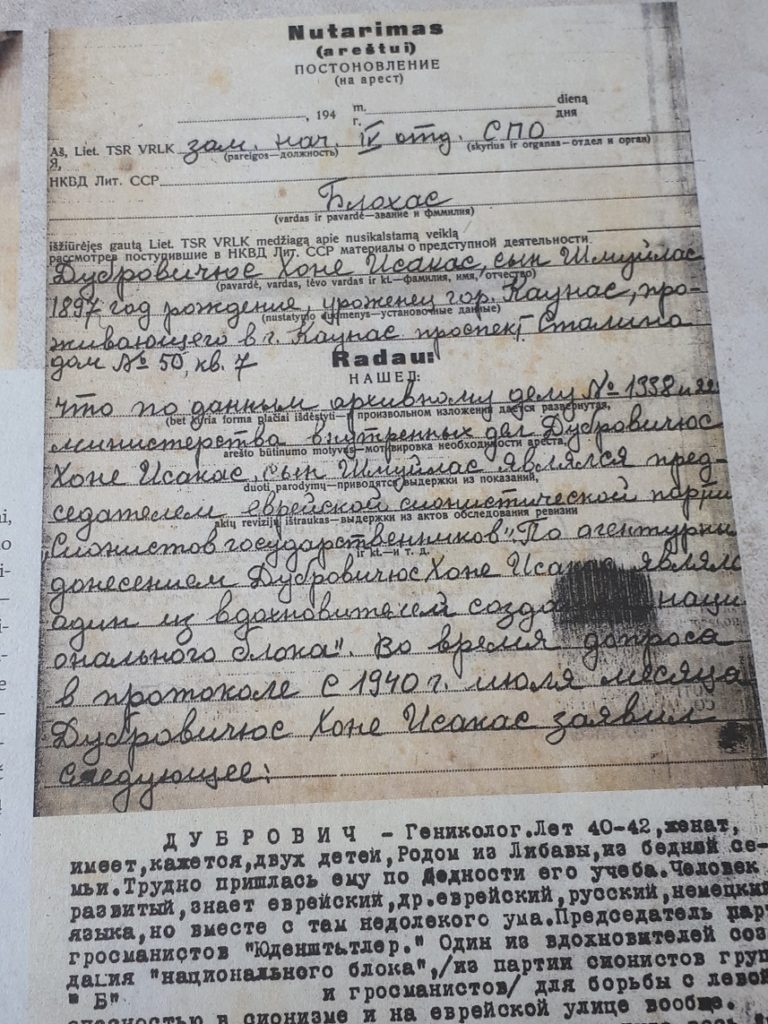

Her father was separated from his family that day, June 14, at the train station. He was taken by a different route to a camp in Mordovia. He was transferred to a different camp after some time. Her grandfather, the gynecologist Isaakas Chonė (Elchananas) Dubrovičius, was the chairman of a Zionist party. Before being deported he lived and worked in Kaunas, owned a home and practiced medicine as a gynecologist, having been graduated in Gießen, Germany.

Lithuanian Jews and Jewish doctors faced several waves of Stalinist state anti-Semitism accompanied by oppression of medical workers and their families, including deportations, restrictions on professional activities and being terminated from their jobs. The accusations centered around property ownership, participation in public organizations and so on.

Rozalija found her grandfather’s case-file in the archives and began reading through it, without understanding it at first. The NKVD–the predecessor of the KGB–made lists of people to be deported well before the actual deportations and the celebrated Kaunas gynecologist became a political prisoner deported to the Potma camp in the autonomous Soviet socialist republic of Mordovia. He cut down trees there. Later he was removed to Krasnoyarsk. He wasn’t allowed to practice medicine in exile, he could only act as a paramedic. All documents were removed from him. He was only allowed to travel from the camp to visit his family, also in exile in the town of Slavgorod in the Altai region, in 1955. Rozalija was 3 years old when then, when she first met her grandfather. In 1958 his status as a persecuted person was changed and Isaakas Chonė Dubrovičius was again allowed to practice medicine. Colleagues from Kaunas wrote letters to authorities citing the lack of doctors in Kaunas and asking he be released in order to return, to no avail. It was only when he was able to obtain a copy of his diploma from Germany that he was allowed to practice gynecology, but deportation and hard labor in the gulag had ruined his health. He performed surgeries for three years, but when his hands began to shake uncontrollably he was no longer able to operate.

Their grandfather never spoke about it, and the grandchildren grew up not knowing much about his experience in the camps and exile. Rozalija says she learned about her Jewishness as a child, when people on the street called her and her mother “yevreika,” a word for Jew with pejorative connotations at that time.

Rozalija’s mother’s brother was also a doctor following in his father’s footsteps. Rozalija talks about how she became a doctor. The family wasn’t allowed to return to Lithuania from the Altai. No matter how many letters and requests they wrote and submitted, the answer was always no. Her parents were only allowed to return in 1991 and settled in Vilnius.

Her father kept looking for ways to leave the small town of Slavgorod in the Altai region where they had been forced to live so long, and finally he received an invitation to work in a factory in Kazakhstan. The entire family moved there. A few years later they were able to move the grandparents there as well. Her grandfather was already ill then. He didn’t survive long, only until 1970. He wasn’t allowed to go back to Lithuania and never saw his home again.

Her grandfather had a good life in Kaunas before the war. He worked at hospital, was a respected and honored member of the community and was active in Zionist activities. After graduating from Gießen he was required to take and pass a Lithuanian-language examination in order to work as a doctor in Kaunas. Rozalija keeps some of the family heirlooms at her house, including his chess set, a portrait and photographs. Several of his personal items have been donated to the Ninth Fort Museum in Kaunas.

Her grandfather’s family had been very poor, his mother had been a seamstress and his father a manual laborer. They left Kaunas to live in Liepāja, Latvia. They had five children. All of them pursued an education and acquired higher education abroad because Jews were banned from attending university at that time. They earned their own money to pay for their studies and her grandfather completed high school by correspondence before entering university. Chonė Isakas worked as a tutor for children.

Great-Grandparents Murdered in the Holocaust

Rozalija Černakova remembers her parents spoke Yiddish in the gulag and that she and her brother learned the story of grandfather Dubrovičius up to the war from their grandmother.

Rozalija left their home in exile at the age of 17 to study medicine in Tomsk, which was also a city of deportees. At the age of 39, in 1982, she left for Lithuania. For a time following her studies and before returning to Lithuania she lived in Kaliningrad, until she received permission to live in Alytus, where she learned Lithuanian and worked at the regional central hospital. When Lithuania restored independence her parents could finally return to Lithuania as well. They moved to Vilnius, whither Rozalija also moved, receiving work at the Central Polyclinic. Today she is a doctor at the Santariškės Children’s Hospital and has been for 22 years.

“My mother, who had completed high school in 1948, tried to flee exile with her high school record. Her marks were really good,” Rozalija recalls. “She fled alone. She ended up in Kaunas without any documents. She located her aunt, a former Kaunas ghetto prisoner, whose family had survived, and whose husband was a doctor. She lived with her aunt for a couple of weeks but someone informed on her, that she had fled exile. She was arrested immediately and put in prison for two years, then sent to a camp which was in Vilnius then. From there she was sent back to her place of exile in Altai. The escape was a failure and after completing high school mother didn’t want to study medicine. Forced back to Altai, after some time she married a Jew from Varėna,” Rozalija’s father. “Mother worked as an economist. My mother’s fate was destroyed, she always felt the pain of a life unrealized, a sense of inferiority,” Rozalija said.

Deportation documents for Dr. Chonė (Elchananas) Dubrovičius