The Lithuanian Jewish Community was shocked by an unsigned “explanation” published by the Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance of Residents of Lithuania (hereinafter Center) on March 27, the day before the anniversary of the horrific Children’s Aktion (mass murder operation) in the Kaunas ghetto, a text which, apparently seeking to avoid responsibility, not only seeks to justify actions by Jonas Noreika during World War II but also contains features which are crimes under the Lithuanian criminal code, namely, denial or gross belittlement of the Holocaust. Note that article 170(2) of the Lithuanian criminal code (public approval of crimes against humanity and crimes by committed by the USSR and Nazi Germany against Lithuania or her residents, their denial or grossly diminishing their scope) also applies to corporate entities.

It is unacceptable to the LJC that there might be a collective condemnation of ethnic Lithuanians or any other ethnic group for perpetrating the Holocaust, and therefore it is equally incomprehensible to us on what basis the Center tried to convince Lithuanians, writing in the name of all Lithuanians, of Holocaust revisionist ideas.

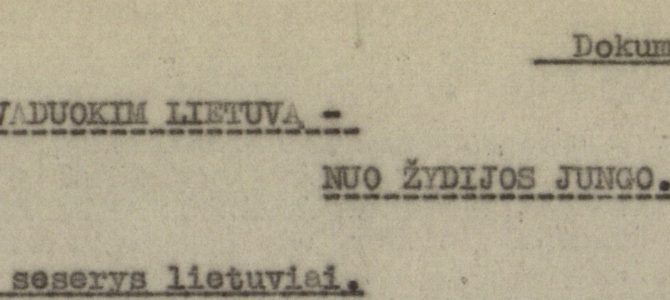

This “explanation” is full of factual and logical errors, for example, one sentence claims “the Lithuanians worked operated against the will of the Germans” while another says “Germany was seen as an ally.” Also, based on a single source, the claim is made that the number of Lithuanians who shot Jews was “lower than in other nations.” The text fails to explain why the greatest percentage of Jews were murdered in Lithuania when compared to the other states of Europe, including Germany, and thus clearly seeks to diminish the fact of Lithuanians’ contribution to the murder of the Jews. The Center text claims “the residents of occupied Lithuania in 1941 didn’t understand ghettos as part of the Holocaust,” not just heaping scorn on the pain of ghetto inmates but also belittling those Lithuanian heroes who rescued Jews at the risk of their own lives and those of their families. The Center’s Noreika apologetica is based on the testimony of his fellow Lithuanian Activists Front members. Note the LAF call to free Lithuania by ridding the country of “the yoke of Jewry” in 1941.

It is the LJC’s opinion that the Center as a state institution founded in law by distorting historical facts, grossly diminishing the scope of the Holocaust and creating a fictional narrative of history is incompetent to fulfill its main task as defined in Lithuanian law, namely, the restoration of historical truth and justice.

Therefore, the LJC asks:

-representatives of the Lithuanian executive and legislative branches to respond appropriately and in a timely manner by condemning this incident of institutional anti-Semitism;

-that the Center take responsibility and retract publicly the above-discussed text, apologize to the LJC for the gross belittlement of the scope of the Holocaust and apologize to the Lithuanian public for misinforming the public.

If within a reasonable time an amicable solution is not found, the LJC, in defense of its interest protected by law but now violated, reserves the right to make sue of the defensive measures and remedies provided in Lithuanian law.

Faina Kukliansky, chairwoman

Lithuanian Jewish Community

The following is an unofficial translation of the Genocide Center’s unattributed “explanation” presented in English to make plain the objections raised by the Lithuanian Jewish Community.

§§§

Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance of Residents of Lithuania

a state institution, Didžioji street no. 17/1, LT-01128 Vilnius telephone (8 5) 231 1033 email centras@genocid.lt

Information entered and preserved in the registry of corporate entities, code 191428780

On Accusations against Jonas Noreika (General Vėtra)

March 27, 2019, Vilnius

In 2015 the Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance of Residents of Lithuania (hereinafter Center) published a finding on the activities of Jonas Noreika (General Vėtra) in Nazi-occupied Lithuania. Over four years many judgments and assessments of Noreika were made publicly. In 2018 citizen G. A. Gochin presented copies of documents and a 69-page text to the Center, publicly claiming that these were proof Noreika supposedly collaborated with the Nazis and committed crimes against humanity. G. A. Gochin also filed a court case demanding that, based on his material, the Center replace its 2015 finding. The Center, taking into account the controversies being stated publicly and after additional assessment of the circumstances of Noreika’s anti-Nazi activities, is publishing this explanation.

1. The Nazi Occupational Regime in Lithuania Operated Differently than in Other European Countries

In solving issues of collaboration during the years of Nazi occupation it is necessary to take into account the type of occupational regime introduced by the Nazis. Lithuania was the only country in Europe which attempted to exploit the German attack and free herself from the Soviet occupation, declaring an independent state and restoring earlier self-government structures (it was hoped the Germans after beginning the war with the Soviet Union and occupying a Lithuania which was no longer a part of the Soviet Union would recognize Lithuania’s independence). Due to these circumstances, the type of Nazi occupation regime introduced in Lithuania was different from the types of Nazi occupational regime in occupied Western and Eastern European countries.

During the June Uprising in 1941 and the fully restored system of self-government which had hitherto existed in independent Lithuania following this, Lithuanians operated against the Germans’ will, their goal was to serve Lithuania rather than the Third Reich. Even so, the Third Reich was seen as an ally in the fight against the Soviet Union.

2. The Germans Sought to Show Lithuanians Were Responsible for the Murder of Jews

Even in the initial days of the occupation the Nazis dashed the hopes of the Lithuanians for independence. The Germans said the highest government belonged to the leaders of the German military, the insurgents of the Uprising were disarmed and the Lithuanian administrations was forced to come to terms with the demands of the German military administration. Especially surprising to Lithuanians was the extermination of the Jews, which had been planned by the Nazis even before attacking the Soviet Union. The special Einsatzgruppe A group under the command of SS brigadenfuehrer Walter Stahlacker implemented this plan in Lithuania. Nazi-organized mass murders of Jews took place in the German-Lithuanian border area, in Gargždai, in Kaunas, Vilnius and Plungė, and quite rapidly in the cities and regions there appeared identical German directives for limitations on the life of Jews and the establishment of ghettos. It is clear from the secret German documents that Sathlecker’s [sic] strategy was to murder as many Jews as possible in the first period of occupation while Lithuanian residents still viewed Germany as an ally in the battle against the Soviet Union.

Among the documents at the Nuremberg Trials was Stahlecker’s report to German interior minister H. Himmler which states Stahlecker’s group “had to establish the indisputable fact showing that the liberated residents themselves undertook the harshest methods against the Bolsheviks and Jews. This had to be done in such a way that the German directives weren’t made plain. … To our surprise, it wasn’t easy to incite broad pogroms against the Jews” (Henry A. Zeiger, The Case against Adolf Eichmann, New American Library, 1960, pp. 64-67 [please note the excerpt is translated from the Lithuanian translation by Genocide Center and is not a citation from the original]).

Lithuanian delegations approached the German leadership at various levels regarding the extermination of the Jews and received the reply that the Jewish question was the exclusive province of the Germans. In response to Provision Government defense minister Stasys Raštikis’s conveyance of the Lithuanian nation’s severe protest against violence against the Jews, general Franz von Roques replied that this was not being conducted by the military but by the Gestapo and that “this operation will conclude quickly” (Stasys Raštikis, Kovose dėl Lietuvos, vol. II, p. 307). Former minister of independent Lithuanian father Mykolas Krupevičius together with former president Kazys Grinius and former minister Jonas Aleksa also expressed to the Nazis in the name of the Lithuanian nation a protest on the destruction of the Jews, noting: “Jews were murdered [in] the nation’s reaction during the time [of the Uprising], but they were killed not as Jews, but as Bolsheviks. More Lithuanians than Jews suffered from this vengeance of the nation. There were morally rotten Lithuanians who aided the Nazis in murdering Jews and seizing their property, but such were, comparatively, a small number, less than among other nations who found themselves in equivalent situations. Rabbi Sniegas, who often visited bishop V. Brizgys, often orally thanked him for the support of all Catholics and especially the clergy, saying that the attitude of Catholics would never be forgotten by the Jews. The Nazis, for some sort of reason, told the world that the Jews in Lithuania were not being exterminated by them, but by the Lithuanians themselves. They even prepared books for this matter, “How the Lithuanians Murdered the Jews.” A Jewish Gestapo agent, Jewish press journalist Serebovich, was ordered to write these, a man who walked the streets of Kaunas constantly with a briefcase clutched to his side as his people were imprisoned in the ghettos and mass murdered (Mykolas Krupavičius, Lietuvių ir žydų santykiai Hitlerio okupacijos metu, Laiškai lietuviams, vol. 37, 1986, Nos. 6, 7).

3. A Large Number of the [Members of the] Self-Government Became Involved with the Anti-Nazi Resistance, Although There Were Some Collaborators

A month and a half after the Germans issued demands unacceptable to the Lithuanians, the Provisional Government halted its activities and the Lithuanian Activist Front, the organizer of the Uprising in Lithuania, withdrew to engage in anti-Nazi activities and created the organization the Lithuanian Front. Four members of the Provisional Government were imprisoned for anti-Nazi activities, while some others (including former head of the Lithuanian Provisional Government J. Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis) had to go into hiding, and still others contributed to rescuing Jews.

Even so, local self-government institutions, although they were led by the German regime, remained in operation: this was an attempt to soften the impact of the new occupation upon the people. Many self-government [public] servants joined different Lithuanian anti-Nazi resistance organizations or at least supported the Lithuanian national anti-Nazi resistance. The strategy of the anti-Nazi Lithuanian Front was to preserve the residents of Lithuania to the maximum extent possible, to manoeuver between the demands of the occupational regime and their non-fulfillment and to avoid impassioned confrontation and emotional declarations. Jonas Noreika as the head of the Šiauliai regional administration also acted as the commander of the Šiauliai military district’s underground Lithuanian Front and carried out the directives of the leadership of the resistance, and in 1942 he was also appointed commander of the Mažeikiai military district of the Lithuanian Front (Mindaugas Bloznelis, Lietuvių frontas, Kaunas 2008, p. 95, p. 257).

By concentrating the efforts of the Lithuanian anti-Nazi underground and public servants, it was possible to sabotage more than one mobilization announced by the Nazis of Lithuanians to the German military, and also to disrupt the formation of a Lithuanian Waffen-SS legion (of all the European countries occupied the Nazis were only frustrated from forming SS battalions based on ethnicity in Lithuania and Poland). The Jew Haim Lazar testifies that ghetto prisoners had come to agreement with Lithuanian police for the flight numerous times of prisoners through the Vilnius sewers in the courtyard of the Vilnius police (Lester Eckman, Haim Lazar, Jewish Resistance, New York 1977, p. 37).

Nonetheless some people who served in the self-government structures, especially those which the Germans assumed directly to themselves (Lithuanian police battalions, security police) did collaborate with the Nazi regime and contributed to the extermination of the Jews.

4. The Occupational Regime Was Able to Involved Noreika in the Administration of Affairs Related to the Isolation of the Jews

In its finding of 2015 the Center explained why the story of one person (Plungė kommandatura employee Aleksandras Paklaniškis) that Noreika allegedly was responsible for the mass murder of the Jews of Plungė was unfounded: it contradicted the testimony of six other people as well as other factual material. Nonetheless, the Center recognizes the occupational regime did succeed in drawing Noreika into the making of decisions connected with the isolation of the Jews. On August 22, 1941, Šiauliai district chief Noreika forwarded to rural district aldermen and burgermeisters of small towns an order by Šiauliai military district commissar Hans Gwecke of August 14, 1941, to move Jews into the Žagarė ghetto, and also an order on the procedure for liquidating Jewish property. It’s worth noting these orders were not issued on Noreika’s initiative, they were directives from the German administration forwarded by Noreika acting as district chief. It’s worth noting Noreika did not forward any orders concerning the Šiauliai ghetto because under the laws on municipalities in force at that time the burgermeister of Šiauliai was not subordinate to the chief of the Šiauliai district.

5. Residents of Occupied Lithuania in 1941 Didn’t Understand Ghettos as Part of the Holocaust

Under Lithuanian and international law genocide and crimes against humanity are defined as an intentional act committed with an understanding of the consequences of one’s actions.

In the summer of 1941 the majority of Lithuanian citizens including Jews did not understand ghettos as one of the stages in the extermination of the Jews. Before the German occupation in Lithuania people had heard of oppression of the Jews in Germany and ghettos in Poland, but it was not known that isolation would lead to mass murder.

Following Nazi-organized massacres of Jews in Kaunas, SS brigadenfuehrer Stahlecker told the Jews the only to defend them from further pogroms was if they moved into ghettos. “After the first pogrom the Jewish council was called in and they were told that … the establishment of a ghetto was the only means for creating normal living conditions. Then the Jews suddenly said they would try to get their people as quickly as possible into Vilijampolė [neighborhood, aka Slobodka] where they planned to set up a Jewish ghetto” (from Stahlecker’s report to Himmler; Henry A, Zeiger, The Case against Adolf Eichmann, New American Library, 1960, pp. 64-67 [note this quote is translated from the Lithuanian and is not from the original text cited here]).

Lithuanian Jewish Community representative and Vilnius ghetto researcher Ilja Lempertas says that until the end of 1941 and even later Jews in the Vilnius ghetto couldn’t conceive of their existence in ghettos as meaning their physical extermination: “Let’s keep in mind the people of that time did not know about the Holocaust, we know about it, having before us the entire picture of the events of World War II. They saw bad behavior but didn’t know the Holocaust had begun. Besides which, in the fall of 1941 the Nazis instituted the death penalty for hiding Jews. It was said a man who had helped Jews was hanged on Cathedral Square [in Vilnius] that fall. And a placard was hung [on the body] saying this would happen to everyone” (Zigmas Vitkus, Vilniaus getas–kai žmonės bandė įsivaizduoti gyvenimą, Kelionė, 2013).

People are confused because the first mass shootings in Lithuania took place before the establishment of ghettos, and because of the different life-spans of the ghettos: the small ghettos were destroyed along with their residents very quickly, while the large ghettos of Vilnius and Kaunas survived several years, and the Šiauliai ghetto was only liquidated in 1944. There were cases where Jews who had been freed and were in hiding couldn’t deal with the tension and returned to the ghettos of their own volition; it seemed safer there to them.

Šiauliai military district commissar Hans Gwecke–filmed recordings of his memories are preserved at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington–said that at that time they didn’t think the ghettos would end with the extermination of the Jews. Gewecke said one of the Nazi idealogues “Rosenberg said the Jews in Šiauliai had lived in a ghetto before the war as well. Rosenberg considered closing them in in ghettos a humanitarian matter.” The Allies captured Gewecke after the war but after interrogation let him go, despite his direct orders on the Žagarė and Šiauliai ghettos.

Accusations similar to those made against Noreika (collaborating with the Nazis and contributing to the isolation of Jews) were also made against the head of the Lithuanian Provisional Government, Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis and interior minister Jonas Šlepetys. In 1974, at the direction of the U.S. Congress, the U.S. Department of Justice performed a full investigation regarding these accusations and, finding no evidence of crimes in their activities, removed them from the list of suspects (Genocido tyrimo centras nepasiduos vulgariam spaudimui [Genocide Research Center Won’t Surrender to Vulgar Pressure], delfi.lt, 2019).

At the international level there is still discussion going on whether structures keeping order inside the ghetto should be judged Nazi collaborators. The Jewish council (Judenrat) and the internal Jewish ghetto police carried out Nazi orders inside the ghetto: they selected residents unfit for work (the Nazis shot them), passed on German directives on surrendering property, supervised the keeping of internal rules and so on. According to Jewish historian Lempertas, “The Judenrat is truly controversial. But that’s how people who don’t know history see it. Taking a deeper look, we see that black and white history doesn’t fit here.” It is worth noting that, at the initiative of the Jews of Lithuania, chairman Haim Khanon Elkes of the Kaunas Jewish council and Kaunas ghetto police chief Judas Zupavičius have been commemorated with honorable plaques.

6. Noreika’s Actions Shouldn’t Be Judged as Collaboration, He Was an Active Participant in the Anti-Nazi Underground

Šiauliai district chief Jonas Noreika’s activities should not be assessed as collaboration under the customary concept of collaboration indicated by the State Lithuanian Language Commission (traitor to one’s country, cooperating with the institutions of the occupying country, doing harm to the statehood of one’s country and the interests of citizens) for the following reasons:

–Noreika was appointed chief of the Šiauliai district by the Lithuanian Provisional Government, not by the Nazis.

–Noreika as chief of the Šiauliai district opposed the mobilization of Lithuanians into the German military and opposed the establishment of an SS legion in Lithuania, thus, he opposed Lithuanian collaboration with the Nazis; for that he was imprisoned for two years at the Stutthof concentration camp. As indicated by German security police and SD commander Karl Jäger, Noreika “led the Lithuanian resistance movement and especially incited against the mobilization of the Lithuanian people announced by the Reich’s commissar” (Stutthof concentration camp cards, Archiwum Muzeum Stutthof, Sygn., I-III-1124).

–Noreika was an active member of the Lithuanian Front, the Lithuanian underground anti-Nazi organization: he set up the staff headquarters of the Kęstutis military unit of the Šiauliai military district and insured such headquarters were set up in the Telšiai and Mažeikiai districts, took care of weapons for the restoration of Lithuanian military forces, distributed the banned press organ of the Lithuanian Front and contributed to the publishing of an underground newspaper in the Šiauliai district. Lithuanian Front researcher Mindaugas Bloznelis includes Noreika among the 53 most noteworthy members of the Lithuanian Front. It’s worth noting the Kęstutis military unit recruited only members who had no taint of collaboration with the enemy (Mindaugas Bloznelis, Lietuvių frontas, Kaunas, 2008, p. 91, 382, 398, 399; Lithuanian Special Archive, f. K-1, ap. 58, b. 27355/3, t. 7, p. 223; Viktoras Ašmenskas, Generolas Vėtra, Vilnius, 1997, p. 341, 428; Petras Jurgėla, Lietuviškoji skautija, 1975, p. 687).

–Well-known Šiauliai anti-Nazi resistance member and Jewish doctor Domas Jasaitis judged Noreika an active memember of the anti-Nazi resistance. In his memoires, Jasaitis writes: “In my opinion Bubas is responsible for the arrest in March of 1943 of Šiauliai district chief Jonas Noreika, a great patriot and resister, and his deportation to Stutthof.” The Lithuanian Encyclopedia, one of whose editors is Jasaitis, says: “Noreika was appointed head of the Šiauliai district by the Lithuanian Provisional Government in 1941. In this post he joined the underground and staunchly defended the affairs of the country from the occupiers. In 1943 following a propaganda trip to Germany he published an article in the Lithuanian press, ‘Šių dienų Vokietija’ [Germany Today], which wasn’t favorable towards the regime of the Nazis (Lietuvių enciklopedija, XX tomas, Boston, p. 409; Išgelbėję pasaulį. Žydų gelbėjimas Lietuvoje 1941-1944, Genocide Center, Vilnius, 2001, p. 45).

–During Soviet interrogation in 1946 Noreika stated: “National activity was closely connected with Šiauliai Hospital director Jasaitis. We used to consider political issues connected with Lithuania’s future. We assessed the international situation and came to the conclusion the Germans would lose the war, but our interest was to maintain cautious contacts with them so the English and Americans would be the first to occupy Germany and with their help Lithuania could maintain herself against the USSR. In pursuing these goals Jasaitis and I agreed to act no matter where we found ourselves.” In 1946 Noreika planned to include Jasaitis, who was in the West, in the anti-Soviet underground organization he was forming; Noreika instructed the student Varaneckas who was being sent abroad to find Jasaitis and through him to make contacts with Lithuanians abroad (Lithuanian Special Archive, f-K1, ap. 58, b. 9792/3, t. 1, p. 128-129);

–Noreika’s comrade Damijonas Riauka testified that “Jonas Noreika didn’t categorize the occupier as ours or foreign: When we asked how we should act with the Germans, Noreika said: ‘The Russians aren’t our friends and the Germans aren’t our brothers.'” Noreika “together with 10 other intellectuals from Žemaitija demanded the German leadership forbid genocide carried out against the Lithuanian and Jewish peoples and to give Lithuania home rule. In February of 1943 he wrote the article ‘Šių dienų Vokietija’ [Germany Today] which unmasked the perniciousness of the Nazi regime upon the Lithuanian nation as well as upon Germany itself.”

–In issuing his final statement to the Soviet court, Noreika agreed with all the accusations of opposing the Soviet regime except for the accusation that he had “voluntarily served the Germans;” Noreika pointedly requested the Soviet court to acquit him of this single point in the accusations (Lithuanian Special Archive, f-K1, ap. 58, b. 9792/3, t. 4; Ašmenskas, Generolas Vėtra, Vilnius, p. 359, 384).

7. Noreika Belonged to the Anti-Nazi Underground of Šiauliai Which Rescued Jews, Noreika Helped Those Who Rescued Jews.

The anti-Nazi underground of Šiauliai, to which Noreika, Jasaitis, deputy burgermeister of Šiauliai Vladas Pauža, Šiauliai Teaching Seminary director Adolfas Raulinaitis and others belonged, was engaged in rescuing Jews.

Some of the most important operators in this rescue network were Children’s Society Šiauliai branch chairwoman Sofija Lukauskaitė-Jasaitienė and her husband, Šiauliai Hospital director Domas Jasaitis, who organized and carried out broad Jewish rescue operations (Žydų gelbėjimas Lietuvoje II Pasaulinio karo metais 1941-1944, Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum, Vilnius, 2011, p. 59). “Not a day went by without at least several Jews coming to the [Jasaitis]

house, seeking food, to get back items left for safekeeping or to seek mediation or some other kind of help, or to leave news which might be useful to another Jews.” Sofija Lukauskaitė-Jasaitienė testifies that “rescuing a Jew was always connected with danger of death to the person [doing the rescuing] and his family. And the circumstances surrounding a rescue were so difficult and complicated that in order to save one Jew, that work required at least 5 to 10 other people.” Jonas Daugėla testifies that for the rescue of Jews from Šiauliai “there was even a separate organization formed from among more notable public figures.” (Išgelbėję pasaulį. Žydų gelbėjimas Lietuvoje 1941-1944, Genocide Center, Vilnius, 2001, p. 59, 196-204).

Jasaitis and Noreika had strong underground and personal ties, were friends and cooperated in publishing and distributing underground press. The newspaper published by the Šiauliai district resistance council printed an article which condemned the murders of Jews and said after Lithuania had restored independence, the perpetrators of these mass murders and their helpers would face trial. Noreika also wrote his anti-Nazi article for the underground publication.

Šiauliai residents who rescued Jews believed in and trusted Noreika and held him in very high regard. Jasaitis called Noreika a member of the resistance, “staunchly defending the affairs of the nation from the occupiers.” Šiauliai deputy burgermeister Vladas Pauža, a member of the Šiauliai anti-Nazi underground who issued identity papers to over 300 people persecuted by the Nazis for which he had to provide explanations to German security agents numerous times, also judged Noreika “a great patriot, not careful enough in his speech, a mercurial and fiery hero of the nation who died for us and for Lithuania’s freedom” (Domas Jasaitis, Žydų tragedija Hitlerio okupuotoje Lietuvoje, Draugas, Chicago, 1962; Išgelbėję pasaulį. Žydų gelbėjimas Lietuvoje 1941-1944, Genocide Center, Vilnius, 2001, p. 214). Šiauliai district finance department director Antanas Gurevičius judged Noreika to be a rescuer of Jews based on the fact “the Vaiguva Children’s Home belonged to the Šiauliai district board of directors. So it was responsible for the welfare of this home and for taking care of all the needs of the children, meaning, also the needs of 7 Jewish children and one elderly Jewish woman who worked there as a secretary for the orphanage” (A. Gurevičiaus sąrašai, 1999, p. 120). Noreika’s comrade Damijonas Riauka testified that during the first days of the war Noreika convinced a Jewish family travelling by cart whom he encountered to turn off the road and hide from the Germans as quickly as possible (Genocidas ir rezistencija no. 1 (39), Vilnius, 2016, p. 50).

Arrested, interrogated and imprisoned by the Nazis, Noreika did not inform on rescuers of Jews or members of the underground. Returning to Lithuania after two years’ imprisonment at Stutthof concentration camp, Noreika established an anti-Soviet underground organization together with an active member of the Šiauliai Jewish rescue network, former Šiauliai Library administrator Ona Lukauskaitė-Poškienė, the sister of Domas Jasaitis’s wife Sofija Lukauskaitė-Jasaitienė.

8. Noreika Sacrificed His Life for the Freedom of the Homeland, Both Occupational Regimes, Nazi and Soviet, Oppressed Him.

Through his own life, Jonas Noreika showed that the welfare of citizens and the homeland were for him more important than personal interests. He actively resisted both the Nazi and Soviet occupations, for which he was imprisoned by both regimes, and murdered by the Soviets. When he was freed from Stutthof concentration camp, he had the opportunity to withdraw to the West, where his wife and small daughter awaited him, but instead returned to Soviet-occupied Lithuania and aspiring to unite a movement of armed resistance, planned an uprising for Lithuania’s liberation.

Jonas Noreika’s humanitarian nature is demonstrated by the following:

–active resistance to the Nazi and Soviet occupational regimes;

–testimonies from comrades;

–self-sacrifice in caring for Stutthof prisoner professor Vladas Jurgaitis who was suffering from cholera;

–the judgment of fell Stutthof inmate father Stasys Yla: “Noreika returned [to Lithuania] to die with those who were dying for their country. As an attorney he knew what awaited him, but love of country was dearer to him than anything else;”

–the prayer Noreika created at the Stutthof concentration camp (Stasys Yla, Žmonės ir žverys Dievų miške, Kaunas, 1991);

–his greeting to his daughter before death: “I want to see you filled only with creative power because hatred is destructive, but love is a creative force” (Vidmantas Valiušaitis, Ką apie Generolą Vėtrą pasakojo jo dukra, delfi.lt, 2018).

9. The Study Conducted by G. A. Gochin Can Be Considered Neither Objective Nor Academic

The Center investigated G. A. Gochin’s conclusions and appended documents, and presented him and the court reasoned assessments. It is the Center’s opinion Gochin’s research should be assessed as an attempt to give foundation to the memories of a single aforementioned witness (Aleksandras Pakalniškis) which are not supported by other sources, and should be assessed as copying Nazi propaganda that the responsibility for the Holocaust in Lithuania lies with Lithuanians and not Germans. The documents he provided were basically known to the Center, among them there are no new arguments of weight providing a basis for changing the Center’s finding of 2015.

G. A. Gochin’s study cannot be considered objective or academic for the following reasons:

–G. A. Gochin fails to apply an external and internal critical analysis of the historical sources he provides and does not assess their reliability;

–G. A. Gochin selected documents not based on objective criteria but in the attempt to give foundation to preconceived positions;

–G. A. Gochin looks at isolated documents without placing them in the whole of other archival documents, known facts, testimonies and circumstances, thus ignoring the general historiographic context necessary for academic analysis;

–the summary conclusions G. A. Gochin presents clearly contradict some of the documents he himself provides;

–some of G. A. Gochin’s statements could be in violation of the articles of the Lithuanian constitution and the universally accepted presumption of innocence.

Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance of Residents of Lithuania