Rabbi Borukh Gorin from Russia gave a presentation of the life and work of Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer at the 2019 Lithuanian Jewish Community Limmud held in Druskininkai this month.

Gorin is editor-in-chief of the Lekhaim magazine and the Knizhniki publishing house. The magazine is published on paper (about 7,000 copies per issue) and the internet, and is read by about 80,000 internet subscribers. The hard-copy magazine is sent out to readers in Israel, Europe and America, as well as 75 other countries. Gorin says Lekhaim is a window on the contemporary Jewish world and contains articles on history, religion and modern Jewish life. It is published in Russian. It often contains information about Lithuanian Jews. Some time ago the magazine featured Chaim Grade, one of the most important writers in Yiddish who was born in Vilnius on April 4, 1910. He passed away in New York on April 26, 1982. Following the death of his widow, unpublished manuscripts by Chaim Grade were discovered and should be published within a few years. Grade wrote about Vilnius.

In Druskininkai Gorin spoke about Bashevis Singer, calling him one of two well-known Yiddish writers, along with Sholem Aleichem. Singer wrote about Polish Jewish life before the Holocaust. Gorin pointed out Singer came from a family of talented writers, with his brother Israel and sister Ester respected writers in their own right. His father was a rabbi and a good storyteller and his mother was a rationalist and aristocrat. Bashevis Singer moved to the USA before World War II and wrote for the Forward, where he published a cycle about a Polish Jewish family. Singer describes Polish Jewish life and he wrote after the war as if the Holocaust had never happened.

Gorin: “It’s difficult for Jews to write of their dead as saints, but there’s a problem in this case: the saints aren’t wholly understood by us, and that’s why they’re saints. Bashevis Singer shows us a destroyed civilization and people who are just like us before the Catastrophe. As we read, we do not feel it is a different civilization, but our very own civilization which might have made the world better…

“It has been said we still haven’t found a cure for cancer because the discoverers of that cure were incinerated at Auschwitz. Thousands of talented people, talented scholars, carriers of civilization perished in the Catastrophe. Singer’s works seem different when we come to a mass murder site and visit empty Jewish quarters and shtetls. He is a great writer because it is very difficult to describe one’s own world which seems as if it hasn’t vanished, it’s still there, as if the tragic end didn’t exist.”

Gorin said Yiddish was Bashevis Singer’s pride and joy, and that once he was angered when a Forward editor tried to tell him how to write. “Don’t try to teach me Yiddish! I know how to write in Yiddish!” Singer said.

Although his father wanted him to be a rabbi, at the age of 20 Singer decided to forgo continued religious studies and became a secular writer. Gradually he was influenced by his older brother Israel who was a recognized writer. Bashevis Singer left for the USA in 1935, worried by the growing threat of the Nazis and worsening living conditions for Polish Jews. His older brother was living there already.

The Forward in New York published his “Moskat Family” as a series of installments over a year and a half. The story was received as a novel about Central and Eastern European Jewish life and described the worsening of conditions for Jewish families who had lived well before over 50 years up to World War II. It was published as a book in 1945 and Bashevis Singer dedicated it to his late brother who passed away in 1944. An English translation was published in 1950.

Bashevis Singer continued to write and speak Yiddish for decades in America. His work was published in Yiddish first, then followed by translations to English. The writer carefully supervised the translations and censored large sections of the translations, rejecting the most colorful passages on Jewish life and culture, Gorin said. Bashevis Singer, Gorin said, said it was in any case impossible to convey the beauty of Jewishness–the genius of yidishkeyt–to the reader in English.

Gorin cautioned readers should know that Singer’s books in different countries are translated from the English translations, not the Yiddish original, and therefore are missing about half their value. He said those who really want to acquaint themselves with Singer’s work need to find his books translated from Yiddish.

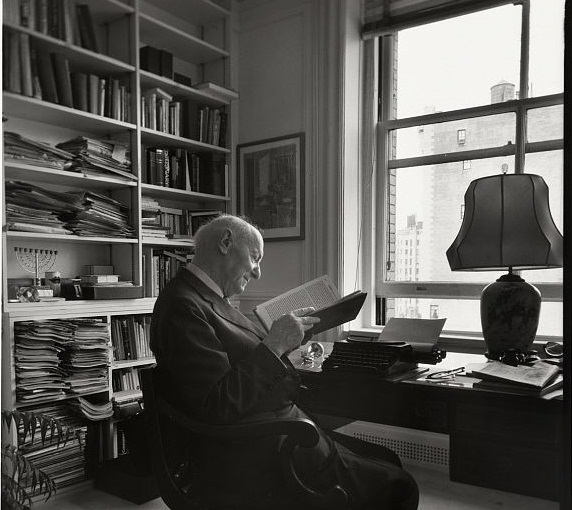

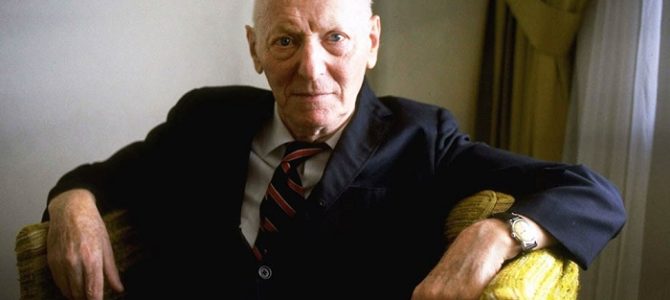

It’s said Bashevis was a humble man and had his own irreproachable style: he liked to wear simple business suits and favored milk bars and writers’ bars. He had a lifelong passion for metaphysics as well.

When Singer was presented the Nobel prize for literature in 1978, he surprised the audience by speaking Yiddish. In announcing the prize, the Swedish Academy also honored Yiddish in Yiddish: “a loshn fun golus, ohn a land, ohn grenitzen, nisht gshtitzt fun keyn shum melukhokh” or “a language of exile, without a country, without borders, unsupported by any state.”