Books link us to freedom, books connect us to the world.

–Yitzhak Rudashevski, December 13, 1942, Vilnius.

Teaching the Holocaust to children is a difficult matter. At what age is it appropriate to expose children to man’s greatest inhumanity to man and the horrible atrocities which took place throughout Europe, culminating in the calculated genocide of millions of people? The Maus comic book was one approach, but children aren’t stupid and they get the full impact of the horror anyway, despite the window dressing.

Teaching adults the Holocaust can be just as problematic. A large body of Holocaust literature including straight histories, survivors’ testimonies and even theological works, not to mention a signficant cinematic canon, can lead to burn-out quickly, the Holocaust hangover syndrome. It is too much to take in all at once, the mind rebels.

Some Holocaust commemoration projects and museums have recognized the old maxim, that a picture is worth a thousand words, and often an object–an abandoned shoe, a lost set of house keys, a broken doll–speaks louder to the soul of the visitor than any text, photograph or video.

Somewhere in between the need to pass on the history of the Holocaust to the younger generation and to prevent Holocaust burn-out, a few years ago a film appeared, broadcasted on the MTV music television cable channel and still available on youtube, showcasing the children and young people who kept Holocaust diaries. The idea seemed to be that teenagers would relate more to testimonies of people their own age. This work on the diaries of children in the ghettos and camps began with Anne Frank, of course, but received real impulse from Alexandra Zapruder’s books, articles and interviews on the subject beginning in the 2000s.

The scholar said numerous times her “favorite” child diarist was Yitzhak Rudashevski, the young man who spent his 14th and 15th years in the Vilnius ghetto with his mother and father, hid out after the ghetto liquidation, were discovered together and then murdered, presumably at Ponar outside Vilnius.

Rudashevski features prominently in the MTV documentary as well.

Sir Martin Gilbert in his books “The Holocaust: The Jewish Tragedy” and “Holocaust Atlas” also makes use of Rudashevski’s diary entries as a source confirming the date of events recorded by Kruk and Sakowicz.

Rudashevski’s cousin Sora Voloshin escaped and became a Jewish partisan fighter. When Vilnius was liberated she went back to the apartment where the Rudashevskis hid after the ghetto was liquidated and looked around for surviving mementos. She discovered Yitzhak’s school notebooks he used for his diary. She passed the contents on to fellow partisan Abraham Sutzkever. After Sutzkever moved to Israel he published extracts from the diary in the original Yiddish in his literary magazine Di goldene keyt (The Golden Chain) in 1953. Sora Voloshin donated the originals to YIVO in New York which has sent facsimiles to Yad Vashem and other Holocaust authorities. In 1973 the Ghetto Fighters’ House outside Tel Aviv issued an English translation and there are other translations in Hebrew, French and other languages.

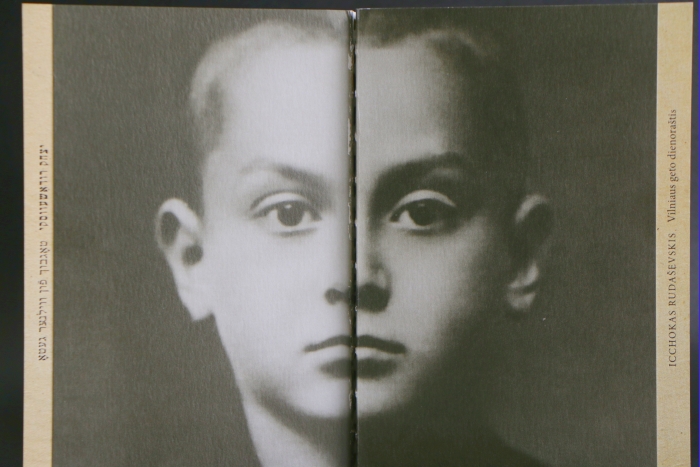

Now the Lithuanian Jewish Community with financial aid from the Goodwill Foundation and the Lithuanian Cultural Council has published a Lithuanian translation of the material Sutzkever published earlier. The book has an “artsy” cover with an open spine, so the muscilage and binding threads are visible, stamped with an off-black ink inscription in Yiddish of Ytizhak Rudashevski’s name. One half of the book is right-to-left Yiddish, the other half left-to-right Lithuanian. The cover is half of Rudashevski’s face; when opened, the coverless spine disappears and both halves of the face come together.

The book contains a long introduction by the translator, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, and a short note from Lithuanian Jewish Community chairwoman Faina Kukliansky haling its appearance. The paper is thick, “Munken Lynx 120 gr.” for the body text and 280 grade for the four cover pages (the face front and back covers are followed by what amounts to title page in Yiddish and Lithuanian written vertically from bottom to top).

The book was shown at the Vilnius Book Fair last month with a small event including the translator and the Yiddish editor, Akvilė Grigoravičiūtė, who is now working on her doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne. Another launch for the general public is planned for later this month, and the book will be sold at select outlets in Lithuania. Copies are being made available for shipping to international customers for €35 including shipping with payment receivable via PayPal. The retail price in Lithuania is €20. For more information, write info@lzb.lt

Yitzhak Rudashevski aka Icchokas Rudaševskis, “Icchokas Rudaševskis. Vilniaus geto dienoraštis,” translated by Mindaugas Kvietkauskas ex Di goldene keyt, Abraham Sutzkever, ed., Tel Aviv 1953; Vilnius: Lithuanian Jewish Community, 2018. 354 pages. The book contains numerous photographs and document facsimiles.

ISBN 978-9955-9317-3-7

§§§