by Dr. Aušra Pažeraitė

The Mekhilta d’Rabbi Ishmael in the Midrash details a discussion by Talmudic sages regarding a line from the Bo portion of the readings for the last Sabbath (Exodus 12:2): “This month shall be for you…” Rabbi Ishmael says: Moses showed the new moon to Israel and said to them: In this way shall you see and fix the new moon for the generations. Rabbi Akiva says: This is one of the three things that were difficult for Moses to understand and all of which God pointed out to him with His finger. And thus you say: “And these are they which are unclean for you” (Leviticus 11:29). And thus: “And this is the work of the candelabrum” (Numbers 8:4). Some say it was also difficult for Moses to understand ritual slaughter, it being written: “Now this is that which thou shalt offer upon the altar; two lambs of the first year day by day continually.” (Exodus 29:38).

Modern scholar of Jewish philosophy David Boyarin says this midrash is one of many examples which plainly, almost spelling it out, show how St. Augustine was correct in saying Jews read Holy Scripture “erotically” [erotically charged by ocular desire]. But here “eros” doesn’t mean imprisonment to the material or carnal for its own sake. It is, rather, a certain method or way to understand the life of the spirit, the religious life, based on what is here and now, on the concrete physical world. Rav Moshe Rosenstein of Kelm (Kelmė) in his explanation of the way in which the wisdom of the world differ from the wisdom of the Talmudic sages gave as an example a small bird which once flew through a window into a home and couldn’t not find the path to fly back out because by nature it sought the way on high, whereas in this case it only needed to look downward. In this way the worldly-wise can exalt their wisdom so much that that which is “low,” the simple truths which aid in finding the answers, may be hidden (Basics of Knowledge, I, 24).

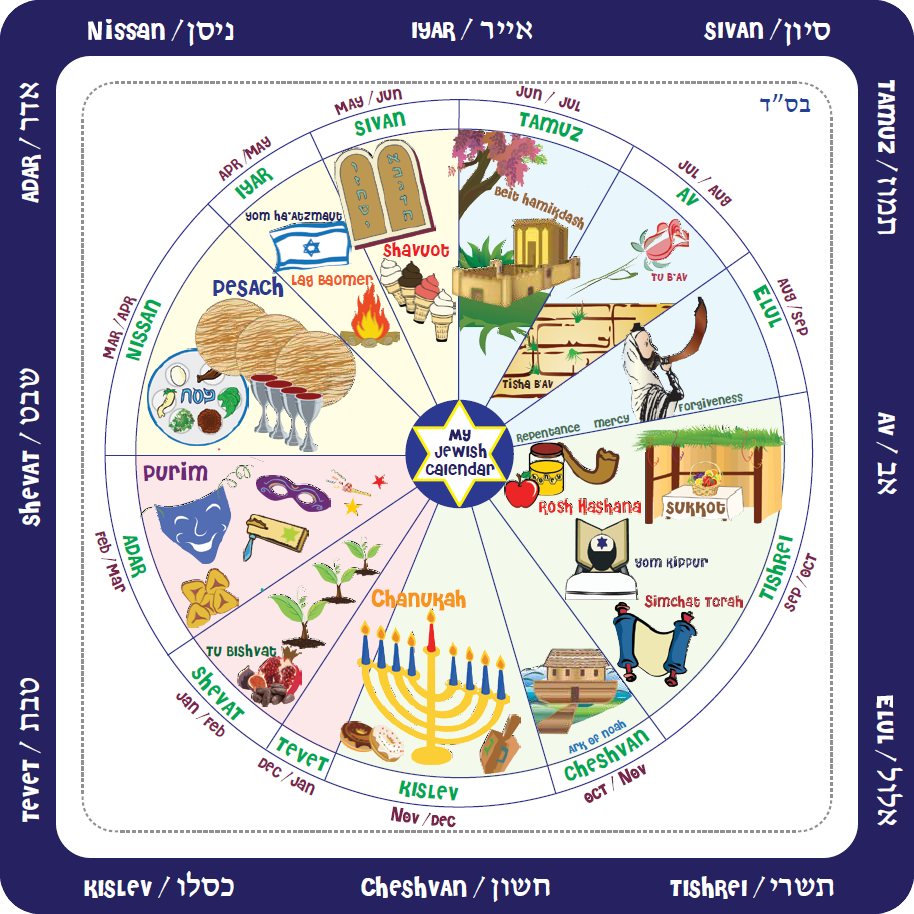

Regarding the beginning of the month, from the passage provided above one understand the new month begins with the observation of something physical, i.e., the new moon [the crescent moon, not the astronomical notion of the new moon as the invisible phase of the moon in apparent conjunction with the Sun and Earth]. The word for month in Hebrew comes from the root for new and is rather symbolic in that regard [the word for month, hodesh, most likely comes from the word in use during the period for the new or crescent moon–translator]. Thus each new month is a new beginning which is accompanied liturgically by the Hallel prayer which praises the Creator of the heavenly bodies. It was also, according to the Torah, the first commandment which that entire community received. Rosh Hodesh [“the head of the month” or first day of the month] is the foundation for the entire existence of this calendar, making possible both the calendar and the holy days.

The Jewish or Hebrew calendar must perform two functions: to fix religious holidays so they are held at the right time, as ordered in the Torah, rather than through whimsical manipulation of calendrical dates, and to reconcile the lunar with the solar calendars. This is explained in Deuteronomy 16:1, “Observe the month of Abib, and keep the passover unto the LORD thy God: for in the month of Abib the LORD thy God brought thee forth out of Egypt by night,” since if only the lunar calendar is followed, which is approximately eleven days shorter than the solar calendar, the holiday would continually creep backwards over the years, moving into winter, then fall, then summer. The lunar and solar calendars have to be reconciled in this way to fulfill both commands: lunar phases allowing the celebration of renewal on each rosh hodesh [first day of the month], and Passover in the spring of every year. Such harmonization isn’t a simple matter and many different systems exist in the world to effect the same thing.

The lunar phases aren’t exact to begin with. Many variables account for the differences, including gravity and eccentricity in the lunar orbit itself. For comparison, many other calendrical systems are provisional and approximate for both the lunar and solar year, and time calculation over the years can lead to such great discrepancies between calendrical and actual positions of heavenly bodies, calendrical seasons and actual seasons, that the first month of spring [Abib in the passage above] moves back to the fall, or that the first winter month ends up in summer. This occurs with some Islamic and Zoroastrian calendrical systems. In ancient Egypt they used a solar calendar with a year of 365 days and a calendar based on the star Sirius with the year beginning around July 19 on the Julian calendar, the “dog-days” when the Dog Star, Sirius, first appeared above the horizon to the east of the Nile. They attempted to harmonize the solar (civilian) calendar with the tropical (agricultural) seasons, which are off by about a quarter of a day, but the tropical seasons coincided more or less with the seasons of Sirius. Thus the solar calendar, the official calendar of everyday life and government, and the Sirius calendar, used for agriculture and religion, gradually diverged so much that they came back around and coincided again, which they do every 1,460 Sirius years.

The most popular calendar used today, the Gregorian calendar, was promulgated in 1582 as a reform of the Julian calendar because of discrepancies in the latter leading to divergences between apparent and calendrical positions of solstices and equinoxes. The Julian calendar has a year of 366.25 days whereas the actual yearly revolution of the Earth around the Sun is approximately 365.2425 days. The Gregorian calendar preserves the integral 365 days of the year and compensates the discrepancy with an extra day every fourth year, the leap year (except for years divisible as integers by 100 but not 400, e.g., AD 1900, in other words, excepting century milestone dates as leap years, and excepting that exception once every 400 years).

The lunar year has 354.37 days, and so is about eleven days shorter than the solar year. To make it coincide with the solar year, it has to be injected, or intercalated, occasionally with extra days or even a month. In the Jewish calendar there is a uniform periodicity for intercalating 7 thirteenth months in a 19-year cycle (on years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17 and 19). The intercalated month falls at the month of Adar as an addition. This extra month is called Adar Alef (first Adar, or Adar I) and is added before Adar, which then becomes Adar Bet (second Adar, or Adar II). This cycle is called the R’ Adda bar Ahava period in Jewish tradition, comprising 235 x (29 days, 12 hours and 793 ḥalakim) / 19, i.e., 365 days, 5 hours and 997.6315789 ḥalakim, and in more understandable terms, 365.2468222 days [the ḥelek system divides the hour into 1080 ḥalakim]. The unit of 29 days, 12 hours and 793 ḥalakim used in this equation is the average duration of the lunar month given to Talmudic sages by Rabban Gamliel in the tractate Rosh Hashanah: “I took this tradition from the home of my father’s father: the renewal of the moon happens not less than every 29 and a half days, plus two-thirds of an hour and 73 halakim from the previous hour.” That translates as: 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes and 33.3 seconds (compared to the astronomical month which is 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes and 2.8 seconds, which shows the figure at which the Talmudic sages arrived is extremely accurate). To clarify matter, the sages used the division of the hour into 1080 parts, or halakim, rather than minutes and seconds. This unit is easily divisible by 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 and 10. Thus the minutes consists of 18 parts. In order to meet the requirements of the Torah, months should be constituted of whole weeks, and the year of whole months. The beginning of the month, or rosh hodesh, must coincide with the first appearance of the new crescent moon. Before calculations were employed to establish the first day of every month, the observation of witnesses was used. This was possible when the Sanhedrin, the high court, operated, where in order for a resolution to be binding, the judges had to meet and deliberate, judges who had been handed down authorization, or semikhah [modern usage “smikha”], through a chain which was supposed to reach all the way back in a chain to Moses. According to the Rosh Hashanah tractate, every time the 29-day month ended, the sky was observed for the appearance of the crescent moon. The Sanhedrin set the beginning of the new month if at least two reliable witnesses gave testimony (who was reliable and who wasn’t was a separate question which was also widely discussed) they had seen the rising new crescent moon over the land of Israel. In each instance the Sanhedrin had to determine the circumstances of the sighting and visibility, and, if testimony agreed, the court declared the 30th daywas to be celebrated, saying the month had not been full, that is, it was only 29 days, and this was the day of the new month, or rosh hodesh. If the moon did not appear on the 29th or 30th day, then the month was declared full, and that the next day in any event would be the first day of the new month. Celebration of the first day of the month sanctified to the holy days within that coming month. Whether or not to add a thirteenth month was a decision made by the members of the Sanhedrin, taking into consideration a number of factors.

Once a decision had been made regarding the start of the new month, that had to be transmitted to Jews so they would have time to celebrate the holiday. Almost all holidays (except for Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur) are celebrated mid-month. To counter the danger that Jews living far away from Jerusalem might not get the news and wouldn’t be sure on exactly which day to celebrate the holiday, the sages decided that outside the land of Israel holidays could be celebrated on two days (except for Yom Kippur).

After the destruction of the Second Temple and after the Sanhedrin removed to Yavne, and following other catastrophes such as the Bar-Kokhba uprising, and especially after Christianity began to flourish in the Roman Empire, it became ever more difficult to insure the practice of taking testimony and constituting the Sanhedrin because of the lack of rabbis with semikhah, and to avoid a situation where there was no way to confirm and announce the start of the new month, under Hillel II ca. AD 358/359, the calendar was created for the coming centuries.