It appears we can finally say exactly what all those who today speak publicly about the mass murder of Jews in Lithuania are truly seeking. Either they are doing PR for themselves through this, advertising themselves, because this is trendy in Europe, or their activities are being financed by the Jews themselves.

All of those shocking details, talk about smashing the heads of Jewish infants on trees to save bullets, is nothing other than the scratching of still unhealed wounds with dirty, dilettante fingers.

In this manner the attempt is made to traumatize yet another generation of Lithuanians, our children born in a free Lithuania, because these sorts of actions, instead of inviting repentance or at least sorrow, actually create even greater hatred of Jews, because this is how the natural defensive reaction of the nation operates. Every nation is different, so Germany’s experience doesn’t fit our situation, that is, healing and finally recovering by demonstrating and revealing through education and openness the brutality of the Nazi concentration camps. All that took place in the period after the war, when events were still vivid, but today the murderers and the witnesses have all but died off, so Lithuania must blaze her own trail. It’s not for no reason at all that our intellectuals, chroniclers and commentators say: don’t do it, don’t pick at that wound with your fingers, let it first heal, let it be forgotten. Sometimes forgetfulness is more worthwhile than remembering.

I am from Molėtai. A small town of extraordinary beauty with three lakes inside the town and another three hundred in the surrounding area. There’s no need to say much, everyone knows Molėtai, Lithuanian vacationers’ paradise. During the war, or more precisely, during one day in the summer of 1941, two thousand Jews were shot there. In other words, eighty percent of the population of Molėtai. More than two-thirds of the town’s residents vanished over the course of a few hours and were buried in a mass grave. German Nazis were in command of the massacre. Local Lithuanians did the shooting. These are the cold, hard facts and numbers.

The execution site is now on the edge of town. In Soviet times there was a square with a memorial board there, and next to, right next to it, perhaps even covering part of that gigantic grave, a regional construction organization was established. So two thousand murdered residents of Molėtai lay under and around its fences, covered by construction equipment, bricks, blocks, barracks, store houses, in other words, they were hidden so creatively that I, born and raised in Molėtai, never even happened upon the place, and knew nothing about it.

All of that is still there today, but now it is more of a garbage dump for old equipment and construction waste, and the square itself looks more pathetic than dramatic. It is a place frozen in time, a preserved piece of the Soviet period, with horribly broken concrete paving stones through which grass is taking hold. I’ve seen many similar sites in the Russian and Ukrainian countryside, but there the whole background is like that: dilapidated, rusting, eroding. You can’t call Molėtai a decaying remnant of the Soviet era. Every year Molėtai grows more beautiful, more European, new bicycle paths are going in, footpaths around the lakes, tennis courts are popping up, there are new Maxima and Norfa stores, and only there, where Jews are buried, is there this complete lack of all movement. Last year the memorial sign was ripped off along with the Star of David. If you don’t already know, you’d have no way of knowing what that location is, what the square is for. The only remaining inscription is “Don’t litter.” This is how the largest wound in Molėtai’s history scabs over and heals, this is the way Lithuania chose to solve the problem of commemorating the murdered Jews. Unique, individual, in a way unlike any other. Really, what a brave and courageous country. After all we didn’t bury our Jews so we could erect monuments to them later, but so that they’d disappear. Not just any sign of their lives, but also of their deaths. Because this is our pain, it might traumatize our children, let the wounds heal by themselves.

One weekend in May of this year an Israeli soccer agent by the name of Tzvi went to this small square in Molėtai where more than twenty of his family members are buried. Grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins–all of them oldtimer residents of Molėtai. He placed a small stone on the large rock from which the memorial sign was torn, as is Jewish custom. He stayed there for while, standing there. As he was leaving the little square a group of locals shambled up and began to drink there. Without any reservations, right on top of the grave. When Tzvi stopped and looked at them, one drunk young man left the group and came straight for him, yelling: “What are you looking at?” Conflict was only avoided due to Tzvi’s especially calm manner. Later they even talked. Tzvi asked him why they came here, out of all the nice places and all the wonderful lakes in Molėtai, to drink. The man said it was comfortable there, on the periphery, and no one saw them.

Of course this isn’t some sort of tragedy, it was just a group of Lithuanian drunks who, most likely, didn’t even know thousands of murdered people lay below them, and that they were drinking and urinating right on their bones. They probably simply want to live in a free country and not to know about its dark past. “Let the wound heal first, then we can talk about it.” But the viewpoint of the local government is completely different: it’s intentional. When Tzvi proposed erecting a new monument with his own money to replace the one destroyed last year, the public servants and mayor of Molėtai jumped up to object, saying it was a matter of Molėtai’s honor to erect a new monument, and that’s why the city of Molėtai was taking full organizational and financial responsibility. But wait, there’s more. On August 29, exactly 75 years since the mass murder, Molėtai would hold a memorial march down the town’s main street, the same one along which the Jews were herded to their mass grave. Invitations were going out to descendents of Jews of Molėtai around the world, the president, prime minister and other members of the elite would take part in the march, and many stars would come, the evening would feature a concert, free food for guests, exhibitions. Here we have a real example of intent, a powerful gesture towards reconciliation.

Were you buying that?

It would really be so wise. And so simple. All that’s needed is the desire, the will, and it wouldn’t cost much, perhaps as much as putting in 20 meters of bicycle path, while the profit from that gesture, that sort of commemoration, would be priceless, Jewish communities around the world would hear about the event and in one night we could completely change our reputation in the world–all of it without any public apology which we so fear, simply by showing them that we’re not apathetic any more, we have matured, we understand what happened, and we are on the side of the victims, not the murderers.

Tzvi really does want to set up a new monument at his expense and it is already being made. But the land where the murdered Jews of Molėtai lie buried belongs to the state. Permission is required to put something there. In order to get that permission, Tzvi has been flying back and forth continuously between Tel Aviv and Lithuania, knocking on the doors of the Molėtai government and is being sent from one office to another. In other words, they’re trying to get him lost in our bureaucratic labyrinth until he loses patience and gives up on his plans.

Probably for the first time in my life I am so terribly ashamed of my city. It’s as if the mass murder is on-going: one group tears commemorative plaques off mass grave sites, another group doesn’t allow them to be set back up again, a third group looks on apathetically. Tell me what tone, what intonation I need to talk to that sensitive Lithuanian soul so that one day he might come to the grave and say to himself: here lie my Jews. Children who ran around the yards in town, climbed trees, splashed in the same lakes, their parents who went down the same streets as my parents to work every day, who got angry, who laughed, for all of whom this town was their home, they loved it as much as we do, but one day they were all shot and they can’t talk about it anymore. Someone else has to do it for them. They’re dead.

I can’t even try to image what they felt as they were being murdered. I just try to imagine what Molėtai was like the day after the mass murder. The week after. Completely empty. Silent. About 700 people remained out of almost 3,000. Shops, banks, bagel shops, soccer clubs, the volunteer drama theater–all was swept into that pit. Oldtimers used to say the perpetrators of the mass murder and those who stole the property of the Jews were haunted by a curse: terrible diseases, deaths of loved ones, their children drowned and died in accidents. There is a monument to the murdered Jews of Molėtai at a cemetery in New York. It was erected right after war by Molėtai Jews who emigrated there in the interwar period. The inscription reads: “May God avenge their blood.”

I suspect there are many such monuments around the world with curses on every Lithuanian town and city. That generation of Jews didn’t forgive, and it seems they won’t in the future. I encountered that when I lived in the USA for a half year. When I met Litvaks and introduced myself as being from Lithuania. As I watched, not only did their attitude towards me change, their faces changed. The ancient eyes of a man would look at me as if I might be the offspring of those who murdered his family. And I understand that just fine, because until we name the real murderers, until we condemn them (instead of even building statues to some of them), we will all be murderers of Jews in their eyes. But this isn’t collective guilt, which we are so keen to condemn, but a collective curse, and we brought it upon ourselves.

But Tzvi and those like him belong to another generation. They aren’t discovering their lost land anew, they’re simply interested in seeing the homes, yards and streets of their grandparents, and believe me, they really do not want those crooked old shacks of yours still standing from those days, they are not coming here to take them from you, they lost much, much more than those homes of their grandparents and their stolen furniture.

The anniversary of the mass murder, August 29, about 40 descendents of Molėtai Jews are actually planning to travel to Molėtai from around the world, from Israel, the USA, South Africa, Australia and Uruguay. And there will a procession down the main street, the same route along which their family members were herded 75 years ago. They are doing the march themselves. So far Molėtai has promised not to hinder them and will even stop traffic along that street for a few hours. And that’s all. Yes, it’s as if two Molėtais exist, and the one which exists in this time is granting the parallel city from the past permission to use the street. Imagine: that day about 40 Jews will go to their grave while about 6,000 Lithuanians will peek out their curtains at them. But wait, this already happened, on August 29, 1941. When they were marching the Jews along this street several white armbanders ran ahead and shouted at the windows: “Don’t look!” Whoever looks will be grabbed from their home and will go with the Jews.

Yes, they will march, they will honor their dead, and probably in the end they will erect that monument. But then they’ll leave, and two thousand buried residents of Molėtai will again remain in silent confrontation with us. They will be dead again, and we will be alive, so we will desecrate that stone and continue to drink and piss on their grave.

This is the worst that could happen, but so far this scenario seems the most likely. I don’t know what to do to prevent it from happening. My Molėtai, the one that exists in the present time, doesn’t want to or isn’t able to understand the significance of this event. It needs help. Help to remove that curse of 75 years. I know there are people in Molėtai who would like to join the procession but are afraid. Can you imagine? In Lithuania in 2016 people in the countryside are still terrified, they think it’s not safe to pay their respects to the victims of genocide. I’m inviting everyone who can and who so desires to come. The president, prime minister, the entire left, the entire right, the entire independent, our stars, our familiar and unfamiliar faces, everyone who might be at the lakes in Molėtai that day, to come… You don’t have to do anything, just walk a few kilometers through the town of Molėtai together with our Jews. To be together in silence, to look one another in the eye. I have no doubt someone will begin to cry, such moments are emotional. Someone from their side, someone from our side. And that’s sufficient, to show them and ourselves that we are no longer enemies.

The procession will take place one way or another. The only question is: will our Jews again walk alone, or will be with them this time?

I so want it to be a beautiful sunny day of endless summer. August 29. The day when reconciliation took place.

Full opinion piece available in Lithuanian here.

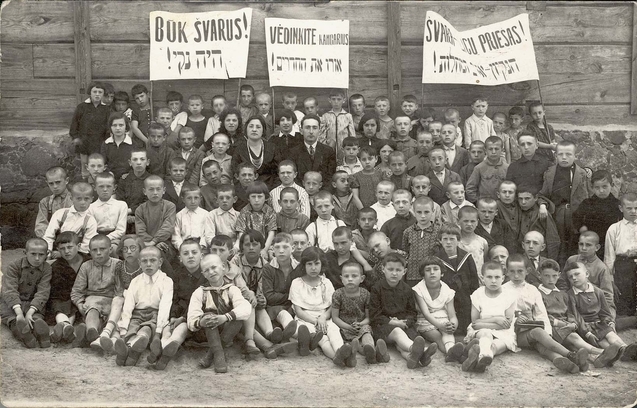

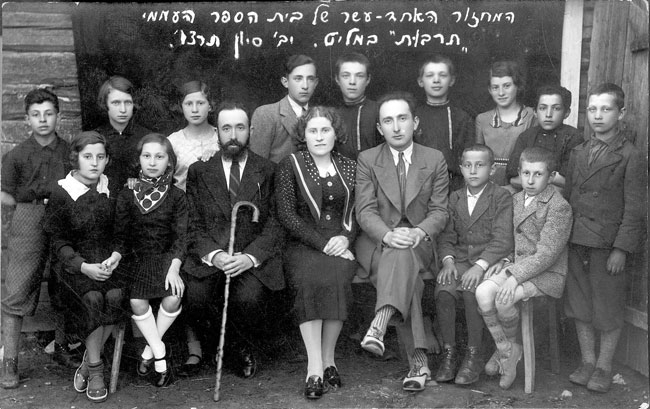

Photos courtesy Yad Vashem