Francine Klagsbrun

Special To The Jewish Week

Watching “Antique Roadshow” on PBS the other night, I was intrigued by one of the items on display. It was a doll someone had inherited, which the show’s expert evaluated at several thousand dollars in today’s market. It had been manufactured, he said, in the early 1900s by Kammer & Reinhardt, a well-known German doll-making company, in business from 1886 to 1932. It was the cutoff date that caught my attention—could this have been a Jewish company that closed down as the Nazis rose to power? The company’s logo on the doll’s back confirmed my suspicion. It showed the initials K and R separated by a Star of David. That star set my mind racing. Did the company’s owners end up wearing the proud symbol of their firm as the oppressive yellow star that marked Europe’s Jews during their darkest days?

This week we commemorated Kristallnacht, the Night of the Broken Glass, when, between November 9 and 10, 1938, Nazi thugs smashed thousands of windows in Jewish storefronts and houses all over Germany and Austria. It struck me as I contemplated, yet again, the horror of those days, how instant had been my reaction to the 1932 closing date of the German doll company, immediately assuming because of that date that the company was Jewish-owned. Those of us who were alive during the Holocaust years, even as children, will always make such associations, always filter 20th-century events through the lens of that century’s Jewish catastrophe.

And what of our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren? It’s been said many times that as Holocaust survivors pass on, we have a greater responsibility than ever to keep their stories alive. But as the 21st century unfolds with its own stories of atrocities and desperate refugees, we also have to make sure that, while deeply sympathetic to suffering everywhere, succeeding generations of Jews understand the uniqueness of the Holocaust and its impact on all of Jewish life.

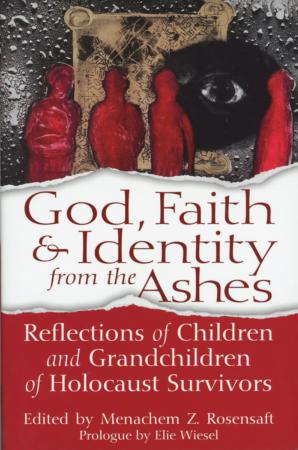

A moving book edited by Menachem Rosensaft and published some months ago, “God, Faith & Identity from the Ashes,” presents reflections by the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors on how the memories transmitted to them affected their own beliefs and identities. They are all different: some, whose relatives discarded all belief in God after their horrendous experiences in the camps, reflect that attitude; others are influenced by the faith a parent or grandparent miraculously held onto in spite of the misery. But what particularly struck me about many of these essays is how deeply ingrained the Holocaust experience can become even two generations later. Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer, for example, tells how her mother guided her grandchildren through Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she arrived at age eighteen. “Here is where they stripped me naked and tattooed my arm,” she says. “Here is where they shaved my head…” and so on. The grandchildren are dumbfounded, but they will never see the Holocaust as just another event in history.

Many of the book’s contributors speak about how their parents or grandparents insisted they have a Jewish education, knowledge being the best path to remembrance. And several reflect on the key role Israel has played in what Rabbi Benny Lau calls “the Jewish people’s resurrection.” One contributor, Merav Michaeli, is the granddaughter of one of the most controversial figures in Israeli history, Israel (Reszo) Kasztner. During the Holocaust, Kasztner made a deal with Adolf Eichmann to save more than 1,600 Jews, and helped rescue thousands of others. Instead of being hailed as a hero he was assassinated by right-wingers in 1957, branded a traitor for associating with the Nazis.

Michaeli’s essay is a reminder of the enormous emotion everything connected to the Shoah aroused in Israel. In 1952, when Moshe Sharett and David Ben-Gurion raised the issue of negotiating with Germany for reparations, people went wild with shock and rage. Menachem Begin and his followers staged massive demonstrations outside the Knesset, where deliberations were being held, with Begin denouncing Ben-Gurion as a “maniac.” In the end, reparations were arranged, and the country benefited from much-needed funds.

The lasting impact of the Holocaust on Israel is part of the narrative of those tragic times that has to be known and remembered as we go forward. The contributors to Rosensaft’s book are, in a sense, new witnesses to the Holocaust. They heard the stories directly from parents and grandparents, and they need to disseminate them. But those of us who were not there yet still have a gut reaction to a date, a mark, a name, need to make sure that our children and grandchildren will also guard the memory of that unspeakable disaster that almost destroyed the Jewish people.

“There can be no Jew who will forget,” Golda Meir said during Israel’s reparations debate. That, ultimately, is the message in commemorating Kristallnacht.

Francine Klagsbrun’s latest book is “The fourth Commandment: Remember the Sabbath Day.” She is currently writing a biography of Golda Meir.

http://www.thejewishweek.com/editorial-opinion/opinion/kristallnacht-through-years