The Lithuanian news and variety magazine Veidas in their February 20, 2015 issue published a long article about the dangers of anti-Semitism in Europe and the prospects for an attack on Jews in Lithuania. The author interviewed several Lithuanian Jews, including Lithuanian Jewish Community chair Faina Kukliansky and head of the Sholem Aleichem Jewish school Miša Jakobas.

“The situation in Europe today is not very promising, it’s not looking good, and I am afraid it might get worse than it is now. I am a child of the post-war era. There are many people who say this generation whose parents experienced and survived the terrors of the war has many problems because we are always afraid. And I am personally afraid of the times past returning. Current events remind me of Nazi Germany, where everything also began from simple things: one person insults another, store windows are broken, and slowly things head towards what happened,” Jakobas commented for the Lithuanian magazine.

Discussing Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s call to European Jews to remember they have a safe harbor in the state of Israel, Veidas magazine quotes LJC chair Faina Kukliansky as skeptical of that approach.

“This is not the very best way to fight terrorism, to simply flee to another country. Israel is a Jewish state, but Jews are diverse, and a Jew living in Europe as often as not considers himself or herself a European, a citizen of his own country. Why should he run away? Is this really a way for everyone to save themselves from terrorism and avoid living in fear?” Kukliansky asked.

According to Veidas, however, Kuklianksy doesn’t think there’s a single simple remedy or choice which fits every situation here, and recalled the atmosphere in Jerusalem following WWII which wasn’t especially favorable towards Jews who survived the war. Veidas quotes her as saying the Jews who lived in Israel before the war condemned rather than pitied the survivors for remaining so long in Nazi Germany and other European states.

“Who would have thought that in the Lithuanian village you neighbor will come and murder you? Did this thought even enter anyone’s head? Then as now, it isn’t possible to find categorical solutions to the problem of living and surviving,” Kukliansky said.

The magazine also spoke with Dr. Bernaras Ivanovas, a political scientist at Vytautas Magnus University in Lithuania’s second city, Kaunas, who believes increasing acts of violence perpetrated by Muslim extremists in Western Europe shouldn’t mean increased tensions or attacks on synagogues and other Jewish heritage sites in Lithuania, but who also cautions there is already sufficient anti-Semitism at work in the country without importing new forms from the EU.

As an example, he recalled an incident at a Kaunas pizzeria in April last year when a British resident of Lithuania complained to police about a drunk customer wearing a Nazi military uniform. He said the most of the Lithuanians there saw no problem at all with the man wearing such a uniform.

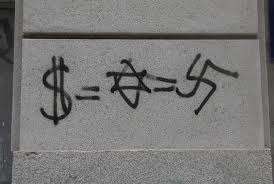

“Let’s also not forget certain publications and caricatures in the press. Society’s tacit approval for that, unfortunately, exists, and there is no introspection or judgment about anti-Semitism in Lithuania. For many people this is a dark forest and they themselves, perhaps considering themselves to be nationalists or simply people who love their country, do not understand it. There is no discussion at all on this topic, and no initiatives have appeared on the part of academics or the media to provide society with a specific understanding of what Nazism is, what anti-Semitism is, how modern anti-Semitism differs from the traditional kinds, and so on,” Ivanovas notes.

He says this is a phenomenon throughout the post-Communist bloc and Lithuania, where for many years the Holocaust was considered “the mass murder of Soviet citizens” rather than a Jewish tragedy, is no different. He said it took many years for West Germany to come to terms with the Holocaust and the past, while East Germany never really did, and even today neo-Nazi groups and anti-Semitism thrive there in comparison.

The Lithuania magazine Veidas said the most insulting thing to the Lithuanian Jewish Community is the annual marches during the most important national holidays featuring the chant “Lithuania for Lithuanians” and other similar slogans.

Veidas quotes Kukliansky as saying this has already become second nature and no one pays attention to it anymore, but that they should, since it shows some of these marchers don’t think all Lithuanian citizens are equal.

“This is a trend and it needs to be fought. These sorts of slogans put us in an unpleasant situation, are somewhat annoying and are an attempt to draw us into unnecessary conflicts and arguments. Anti-Semitism in Lithuania is not a widespread and marked phenomenon and at the current time there is only one pre-trial investigation being conducted. We have many organizations who are concerned with this issue, and sometimes more concerned than we are. The way I see it, however, is that if these sorts of statements and slogans are allowable during one of the largest Lithuanian holidays, then there is still work to be done,” Lithuanian Jewish Community chair Faina Kukliansky commented.

Dr. Elmantas Meilus of the Lithuanian History Institute also provided his insights to the author of the magazine article, calling the Holocaust topic a sort of hidden psychological complex for Lithuanians, most of which they wish to keep hidden.

He said we all understand the Holocaust happened, but Lithuanians don’t want to accept responsibility for it. The dominant view is that Lithuanians are victims who are eternally victimized and who have always had to defend themselves. If something bad happened, the guilt for that is placed upon a handful of “bad guys,” avoiding recognition of responsibility.

“There has always been a hidden, invisible anti-Semitism among a large portion of Lithuanians, and it is still there. The difference is that in 1941 it burst forth. I think the situation from 1940 to 1941, the Soviet occupation, was the cause,” Meilus is quoted as telling the magazine. He said that Lithuanians couldn’t see themselves as especially heroic in giving their destiny over to the Soviets, and much anger built up, as well as the search for someone else to blame. As often happens, the historian said, “those closest to us,” although separate and distinct in this case, “the Other,” the Jews suffered most.