The Gešer Club will hold a holiday meal with a concert and great company at 7:00 P.M. on December 12 at the Draugai restaurant located at Vilniaus street no. 4 in Vilnius. Tickets cost 20 euros. To register contact Žana Skudovičienė, zanas@sc.lzb.lt, +370 678 81514. Tickets are available from Irina Slucker, +370 612 40875, in room 306 at the Lithuanian Jewish Community, Pylimo street no. 4, Vilnius, from 6:00 to 8:00 P.M. on December 8.

Come Celebrate Hanukkah at the Ilan Club

The Ilan Club invites 7-12-year-olds and their parents to come celebrate Hanukkah together at 1:00 P.M. on December 10. There will be a rocking concert, we’ll learn how to make Hanukkah treats together and watch performances and Jewish music by talented performers!

It’s all happening on the third floor of the Lithuanian Jewish Community in Vilnius. For more information contact Sofija at +370 672 57540 or Žana at+370 678 81514.

Hanukkah Greetings

The Abi Men Zet Zich Club greets all our clients and friends on the upcoming holiday of Hanukkah!

At 1:00 P.M. on December 6 students and teachers from the Saulėtekis will perform in a concert called “Let’s Light the Hanukkah Light” on the third floor of the Lithuanian Jewish Community in Vilnius.

At 3:00 P.M. on December 12 you’re invited to the lighting of the first Hanukkah candle at the same location.

For more information contact Žana Skudovičienė, zanas@sc.lzb.lt, +370 678 81514

Magical Hanukkah Journey

Lithuanian Jewish Community children are invited to go on a magical Hanukkah journey with their parents on December 16 and 17.

During the trip we will:

▪ visit the dolphinarium in Klaipėda

▪ search for treasure in the “upside-down house” (http://dino.lt/apverstas-namas-radailiai/)

▪ celebrate Hanukkah on the seaside at the Žuvėdra vacation home

▪ hold the havdalah ceremony to complete the Sabbath

Please note: space is limited. Registration is open until December 10.

Registration and information:

children aged 2-4: contact Dubi Mishpokha Club coordination Alina Azukaitis at alina.roze@gmail.com or by telephone at +370 695 22959

children aged 5-7: contact Margarita Koževatova, Dubi Club, margarita.kozevatova@gmail.com, +370 618 00577

for additional information, contact:

Žana Skudovičienė, zanas@sc.lzb.lt, +370 678 81514

Lithuania Initiated Netanyahu Visit to Brussels

BNS–Lithuania initiated the historic visit by Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu to Brussels to meet with EU foreign ministers, diplomats confirmed Tuesday.

“Lithuania initiated what led to the planned meeting between the Israeli prime minister and EU foreign ministers during a meeting of EU member-state foreign ministerial council December 11,” Lithuanian Foreign Ministry media representative Rasa Jakilaitienė told BNS. Over the last decade Lithuania has become one of Israel’s strongest diplomatic supporters within the EU. Many other EU member-states take stronger exception to the expansion of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories.

Lithuanian foreign minister Linas Linkevičius remarked direct dialogue is necessary to solve remaining disagreements.

In a comment sent to BNS, Linkevičius wrote: “We seek discussion between all EU states on the concerns of the Union and Israel. Direct dialogue is crucial. Only by hearing the arguments presented in discussion can we harmonize what are sometimes very different positions.

Observers say Lithuania’s pro-Israel stance might stem partially from coordination of policy with the United States and might also be due to the history of Lithuanian Jews. Recently Israel and Lithuania have intensified bilateral relations in the military and economic spheres. The Jerusalem Post reports this will be the first visit by the prime minister to Brussels in more than two decades.

Israel annexed the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem following the Six-Day War in 1967. Most EU countries and the EU as a federated entity do not recognize Israel’s declaration Jerusalem is the nation’s capital and cite the need to follow United Nations Resolution 181, or Partition Plan for Palestine, of 1947 which envisaged Jerusalem as an international city. The Jerusalem Corpus Separatum in that plan included Bethlehem and surrounding areas.

Bagel Shop and Israeli Embassy at Charity Christmas Fair in Vilnius

Photo, from right: Prime minister Saulius Skvernelis, LJC chairwoman Faina Kukliansky, Israeli embassy deputy chief of mission Efrat Hochstetler, PM’s wife Silvija Skvernelė

An international Christmas fair fundraiser was held again this year at the Old Town Square in Vilnius. Visitors were invited to purchase handicrafts, Christmas decorations, sweets and other knick-knacks made and sold by the spouses of foreign ambassadors resident in Vilnius, embassy personnel, social welfare organizations.

Photo: President Valdas Adamkus, Faina Kukliansky, former first lady Alma Adamkienė

The international Christmas fair is an annual initiative by the International Women’s Association of Vilnius, which includes women from Lithuania and foreign women temporarily living and working in Lithuania as members.

Photo: Apostolic nuncio archbishop Pedro Quintana

Lithuanian Jewish Community and Bagel Shop volunteers went all out this year to make this event a success. The Israeli embassy’s booth sold Lithuanian and Israeli products and collected almost 4,500 euros for charity, three times more than last year’s amount.

More photos here.

The Litvaks: 900 Years of History

You are invited to a multimedia presentation called “Litvaks: 900 Years of History” by the students of the Saulėtekis school in Vilnius. The Saulėtekis school has presented a number of plays on Litvak culture and the Holocaust. The school has a strong Holocaust education component. In addition, student choirs often perform songs in Yiddish and Hebrew, most recently at the Holocaust commemoration at Ponar at the end of September where they performed the Vilnius ghetto anthem, Zog Nit Keynmol.

The presentation will take place at the Russian Drama Theater at Basanavičiaus street no. 13 in Vilnius at 6:00 P.M. on Wednesday, November 29.

Admission is free.

Japanese Volunteer Teacher Visits Panevėžys Jewish Community

Last week Susumu Nakagawa from Japan visited the Panevėžys Jewish Community. Mr. Nakagawa is visiting Panevėžys for the second time as a volunteer teacher, teaching beginning Japanese at the Panevėžys Technology and Business Faculty of Kaunas Technology University. Mr. Nakagawa is building a bridge of friendship between the two countries, he says. He’s interested in Litvak history and culture, and when he learned there is a living Jewish community in the Lithuanian city, he decided to visit. He was accompanied by art teacher Loreta Januškienė.

Mr. Nakagawa and his family are Christians and interesting in the Old Testament and Jewish history and traditions. Panevėžys Jewish Community chairman Gennady Kofman told Mr. Nakagawa about the history of the Panevėžys Jewish community over tea, and showed him documents and photographs. Mr. Nakagawa posed a number of questions to the chairman, and they touched upon the legacy of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who rescued Jews in Kaunas during the first stages of the Holocaust.

Happy 50th Birthday to Rabbi Krinsky

Happy 50th birthday to Rabbi Krinsky! Mazl tov!

The Lithuanian Jewish Community congratulates Rabbi Sholom Ber Krinsky on his birthday and thanks him for his efforts and sincere work over many years for the good of our community. A young Jewish generation has grown up in Lithuania accompanied by your teaching and good works. Rabbi, the Jewish community wishes you and your family strength and health and that the Light of the Torah would illuminate all your future work.

Mazl tov. May you live to 120!

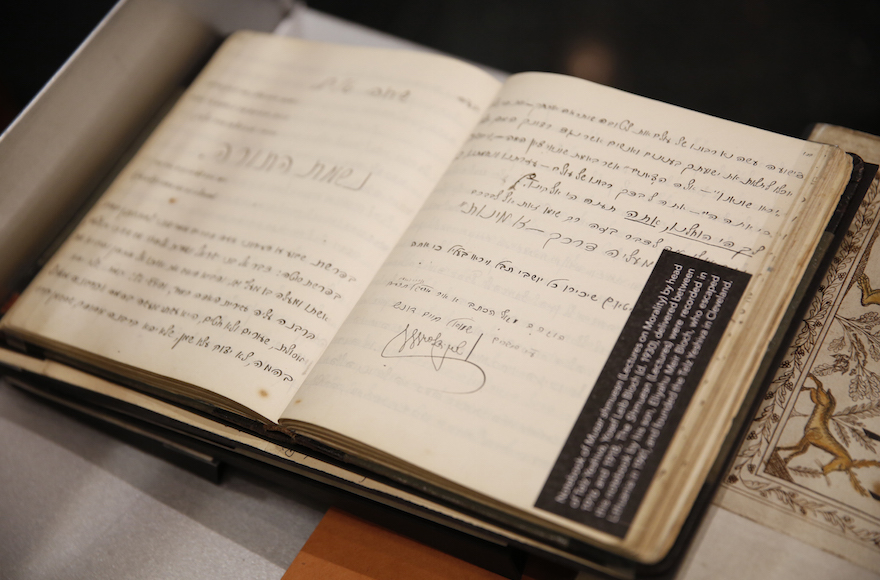

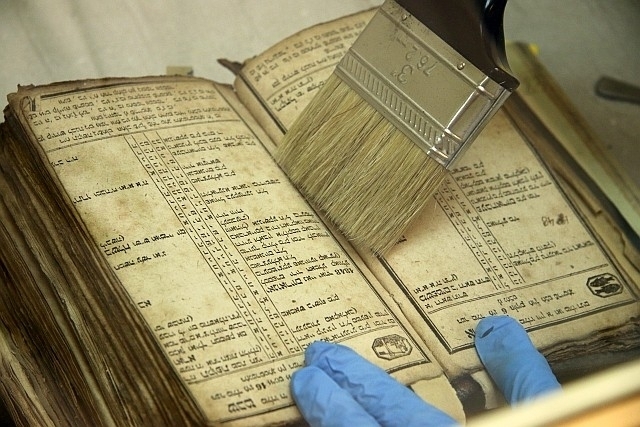

Tens of Thousands of Jewish Documents Lost during Holocaust Discovered in Vilnius

YIVO announces the discovery of 170,000 Jewish documents thought to have been destroyed by the Nazis. Photo: Thos Robinson/Getty Images for YIVO

NEW YORK (JTA)–A trove of 170,000 Jewish documents thought to have been destroyed by the Nazis during World War II has been found.

On Tuesday the New York-based YIVO Institute for Jewish Research announced the find which contains unpublished manuscripts by famous Yiddish writers as well as religious and community documents. Among the finds are letters written by Sholem Aleichem, a postcard by Marc Chagall and poems and manuscripts by Chaim Grade.

YIVO, founded in Vilnius in what is now Lithuania, hid the documents, but the organization moved its headquarters to New York during World War II. The documents were later preserved by Lithuanian librarian Antanas Ulpis who kept them in the basement of the church where he worked.

Most of the documents are currently in Lithuania but 10 items are being displayed through January at YIVO, which is working with Lithuania to archive and digitize the collection.

“These newly discovered documents will allow that memory of Eastern European Jews to live on, while enabling us to have a true accounting of the past that breaks through stereotypes and clichéd ways of thinking,” YIVO executive director Jonathan Brent said Tuesday in a statement.

United States Senate minority leader Charles Schumer, democrat from New York state, praised the discovery.

“Displaying this collection will teach our children what happened to the Jews of the Holocaust so that we are never witnesses to such darkness in the world again,” Schumer, who is Jewish, said in a statement.

Israeli consul general in New York Dani Dayan compared the documents to “priceless family heirlooms.”

“The most valuable treasures of the Jewish people are the traditions, experiences and culture that have shaped our history. So to us, the documents uncovered in this discovery are nothing less than priceless family heirlooms, concealed like precious gems from Nazi storm troopers and Soviet grave robbers,” he said.

Full story here.

LRT TV Program Author Vitalijus Karakorskis Wins Prize for Intercultural Communication

November 16 is UNESCO’s International Day of Tolerance. Under the UNESCO definition in its Declaration of the Principles of Tolerance, tolerance doesn’t mean a tolerant attitude towards social injustice, nor the renunciation of one’s principles and their replacement with someone else’s. It means everyone is free to hold their own convictions and recognizes the right of others to do the same. It means recognizing people are born with different appearances into different social conditions, learn different languages, behavior and values, and have the right to live in peace and preserve their individuality.

The Ethnic Minorities Department under the Government of Lithuania named winners of its prize for intercultural communication November 13. There were 37 separate works in the running this year, including television programs, articles and interviews.

The judges’ panel awarded the prize to journalist, editor and filmmaker Vitalijus Karakorskis for originality and for discovering incredible connections between the ethnic communities resident in Lithuania in his making of an episode of the Lithuanian public television (LRT) program Menora on the topic of Dr. Jonas Basanavičius and Lithuanian Jews, on the 90th anniversary of the death of the patriarch of the Lithuanian state. They also awarded the prize to Siarhey Haurylenka for exceptional treatment of the cultures of Lithuanian ethnic minorities and the Belarusian language in the LRT television series about culture and history called “Cultural Crossroads: The Vilnius Notebook.”

New Fall Issue of the Bagel Shop Newsletter

After skipping a beat this summer, the newest Bagel Shop newsletter has hit the stands. The fall issue includes a complete news round-up from spring to the present, the usual sections and articles about the history of the Bund, efforts to restore Jewish headstones removed from Soviet-era public works projects around Vilnius to their rightful locations and the history of the Jews of Skuodas. The Jewish Book Corner this issue features a book about the tractate Nazir from the Babylonian Talmud and the Telšiai Yeshiva.

Look for the newest issue at the Bagel Shop Café, available for free, or download the electronic version below:

Unique Jewish Archive Emerges in Vilnius

Vilnius, November 3, BNS–As Judaica studies intensify in Vilnius, scholars have identified thousands of important Jewish manuscripts this year which had laid forgotten in a church basement during the Soviet years and were scattered to separate archives for two decades following Lithuanian independence.

Some of the newly identified documents are currently on display in New York City and there are plans to exhibit some of the collection in Lithuania in the near future as well.

Lithuanian National Martynas Mažvydas Library director Renaldas Gudauskas said the identification of ever more documents makes him confident the library currently conserves one of the most significant collections of Judaica in the world.

Hidden at a Church

Vilnius had hundreds of Jewish communal, religious, cultural and education organizations before World War II. YIVO, the Jewish research institute founded in 1925, was an important member of that group. YIVO did work on Jewish life throughout Eastern Europe, from Germany to Russia and from the Baltic to the Balkans, collecting Jewish folklore, memoirs, books, publications and local Jewish community documents, and published dictionaries, brochures and monographs.

New Calls for Jewish Restitution

by Vytautas Bruveris, www.lrytas.lt

After adopting a law on compensating Jewish religious communities, Lithuania should go further and compensate Holocaust survivors for their private property. Both US officials and the Lithuanian Jewish Community are calling for this.

The Lithuanian prime minister’s advisor on foreign policy Deividas Matulionis said: “The issue of returning Jewish private property was raised earlier, but it’s being discussed more frequently now. I wouldn’t say there’s pressure, but the Americans have let us know return of Jewish property remains on the agenda.”

Matulionis was government chancellor in the earlier Government led by Andrius Kubilius when the law creating the Goodwill Foundation was adopted. Under that law the state pays out compensation for Jewish religious community property lost during the war, financing Jewish cultural, religious, educational and other socially useful activities.

The Lithuanian Government is obligated to pay 37 million euros in total to the foundation.

US Diplomat Visits

Matulionis recently spoke with Thomas Yazdgerdi, the US State Department’s special envoy for Holocaust issues, in Vilnius.

The American diplomat also met MPs and leaders of the Lithuanian Jewish Community.

One of the Yazdgerdi’s main topics of discussion was the continuing return of Jewish property.

He said Lithuania following the examples of other Central and Eastern European countries should keep moving forward by returning private property to Holocaust survivors and their descendants or by paying out compensation.

US Officials Urge Lithuania to Return Jewish Property

Vilnius, November 8, BNS–US officials and the Lithuanian Jewish Community are calling upon the Lithuanian Government to return private property to Holocaust survivors and their descendants, the daily Lietuvos Rytas reported Wednesday.

“The issue of restitution of private Jewish property has been raised in the past, but it is being increasingly discussed lately,” Deividas Matulionis, foreign policy adviser to prime minister Saulius Skvernelis, told the paper.

Matulionis recently discussed the issue with US State Department special envoy for Holocaust issues Thomas Yazdgerdi in Vilnius. The Lithuanian prime minister’s advisor told Lietuvos Rytas they hadn’t discussed any specific measures for restitution or numbers.

Matulionis said they talked about possibly compensating Jews for a portion of the value of their property and said that would be more of a symbolic gesture.

Six years ago Lithuania committed to paying 37 million euros compensation for Jewish religious communal property by 2023.

![]()

Public Relations Horoscope

by Sergejus Kanovičius

The weighing ritual from the Soviet era has impressed itself deeply in memory: a plump woman standing behind the counter in a store with a white apron, the apron is somewhat wrinkled and with grease stains, the scales have larger and smaller weights, and she stands and watches, if she has something to way. One weight, and another, then another is needed to reach complete balance, placed on the right-hand plate of the scales, always a deficit, whose weight is measured by this very important woman. The woman is all-powerful. Usually she set some fifty or more grams aside, she also had to supplement her salary. Why do I remember this? I see how today the PR masters and the politicians who have taken up their ideas are joyfully weighing and trying to place a weight or two on a much emptier plate of the scales of historical truth. But one gets the impression that they, just as the woman in the Soviet store did, are setting a bit aside. Sometimes more, sometimes less. Usually more, unfortunately.

You leave their store and unwrap the purchase and hey, either it’s just paper, or else they’ve taken a bit for themselves again. And then you wait again until they decide the time has come to mete out some sort of historical deficit.

As I understand it, the quota for naming the year of the coming 100th anniversary of the state has been used up. Other years are being suggested, maybe the year of the bear on the Chinese calendar, or perhaps the year of the dragon or the cat on the Japanese, one year under the Jewish calendar and a different one according to Christ. Well anyway, we like to baptize, to be baptized and to attend baptisms, it’s fun. Even if there is no baby, we’ll make one up.

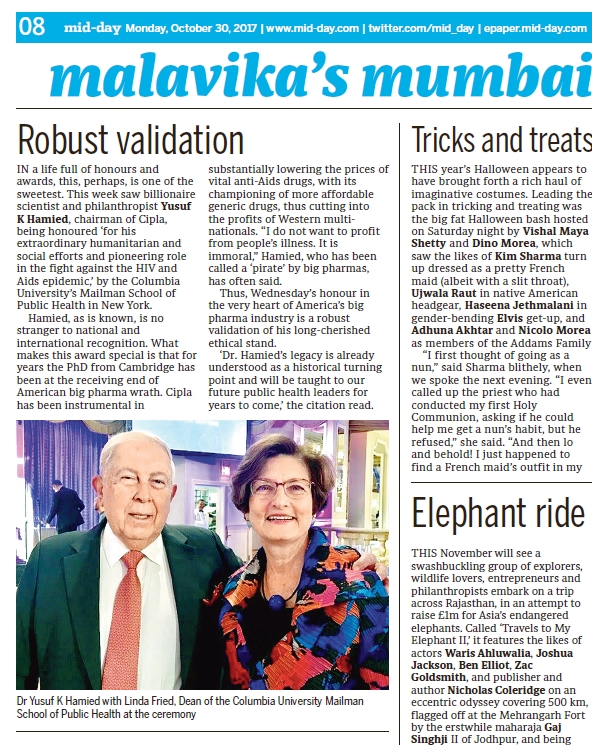

Columbia U Honors Maverick Litvak Pharma King

LJC Challa-Making Event Big Success

The challa-making event at the Lithuanian Jewish Community on October 26 was a fun-filled evening with klezmer music and treats from the Bagel Shop Café. Four generations of women participated, some with their children and grand-children, others with friends, kneading and braiding the dough which was then baked and taken home.

The event was in solidarity with the annual Shabbos Project, now in its fourth year.

More photos here.

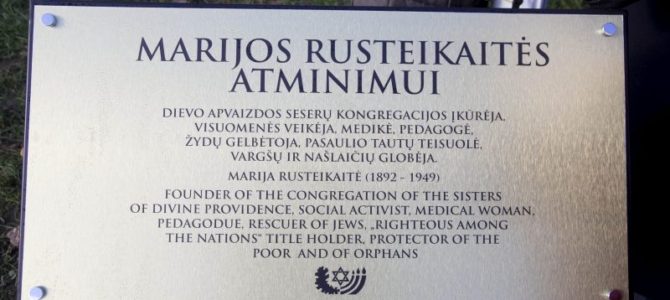

First Plaque Commemorating Rescuers in Lithuania

Panevėžys Is the First to Thank Jewish Rescuers

www.sekundė.lt

The first plaque commemorating those who rescued Jews during the Holocaust has been unveiled in Panevėžys, Lithuania. It honors nun, activist, nurse and teacher Marija Rusteikaitė of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Love of God and her fellow nuns. The stone plaque was unveiled at a ceremony at the intersection of J. Tilvyčio and Krekenavos streets in the Lithuanian city, close to where the Sisters of the Love of God monastery and hospital were located, according to historical documents.

“It was namely this spot, a few dozen meters away, which is the most important historical site of the monastery for us, because this is where Marija Rusteikaitė brought together the nuns, the first sisters of the Love of God, between 1925 and 1936. As soon as she completed the university of medicine in St. Petersburg, the mother superior from Žemaitija joined the St. Vincent de Paul society in order to help the poor people of the city of Panevėžys and surrounding areas. Before that she taught mathematics and geography at the Kražiai pre-gymnasium and Polish at another location,” sister Leonora Kasiulytė, who has long taken an interest in the historical figure, said of the founder of her monastery.

Yuri Tabak to Address Gešer Club

Yuri Tabak, the religious studies scholar, author of numerous books, one of the favorite speakers at Limmud and a wonderful storyteller from Moscow, will visit the Gešer Club of the Lithuanian Jewish Community to speak at 7:00 P.M. on Friday, October 27. Space is limited and registration is required by sending an email or calling Žana Skudovičienė at zanas@scb.lzb.lt or 8 678 815 14.